Question: What can artifacts teach us about the past?

Question: What can artifacts teach us about the past?

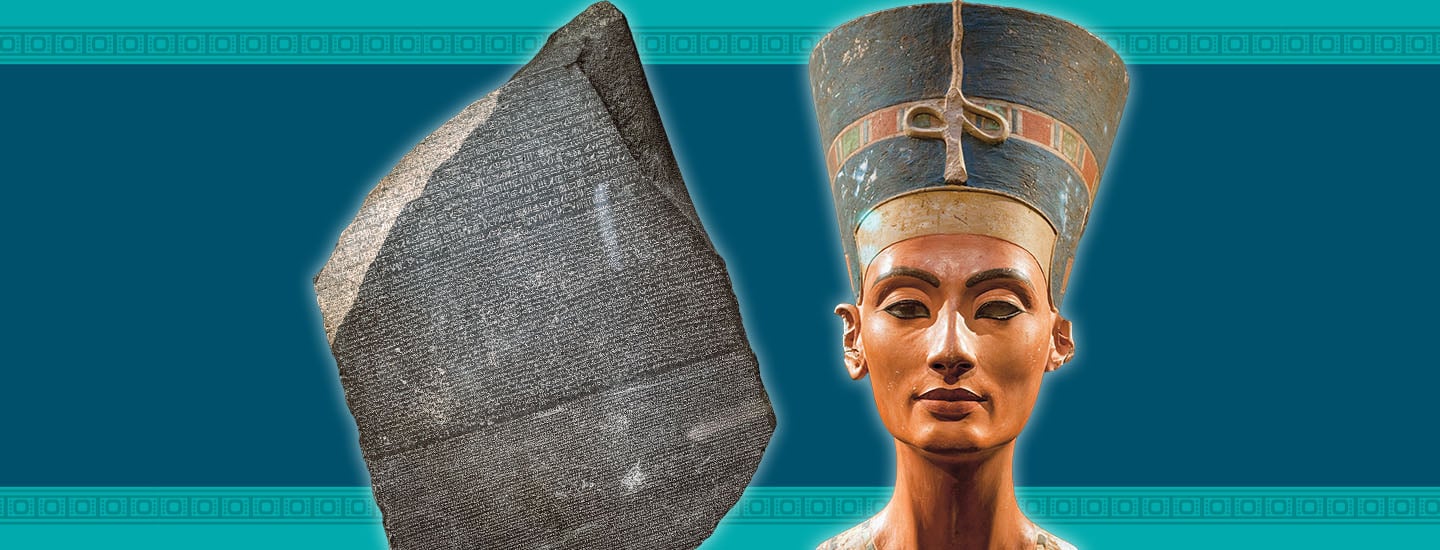

Left: The Rosetta Stone helped historians decode ancient Egyptian writing. Right: Just 19 inches tall, the bust of Nefertiti is one of Egypt’s most famous artifacts.

Shutterstock.com (Background, Rosetta Stone); Thomas Imo/Alamy Stock Photo (Nefertiti)

STANDARDS

NCSS: Time, Continuity, and Change • Global Connections

Common Core: R.7, R.8, SL.1

WORLD NEWS

Should These Relics Be Returned?

A new museum in Egypt sparks renewed debate over who owns the past.

Question: What can artifacts teach us about the past?

Question: What can artifacts teach us about the past?

Jim McMahon/Mapman®

Visitors to the Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza get to step thousands of years into the past. A towering statue of Ramses II, one of Egypt’s most powerful rulers, greets them in the entrance hall. Stairs lead to a majestic view of the Pyramids of Giza in the distance. And then there’s the most mesmerizing sight of all: the entire contents of King Tut’s tomb, on display together for the first time (see “Tutmania Takes Off,” below).

The Grand Egyptian Museum officially opened this past fall after decades of planning. The complex holds more than 50,000 artifacts and spans an area bigger than 90 football fields. It is the largest museum in the world dedicated to a single civilization.

But many Egyptians say the collection is not complete. Some of ancient Egypt’s most important artifacts are on display at museums in other countries—and those countries have no plans to return them. The opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum, however, has reignited the push to get them back.

“Their home should be the Grand Egyptian Museum,” says Zahi Hawass. He is the former head of Egypt’s antiquities program.

Visitors to the Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza get to step thousands of years into the past. A giant statue of Ramses II greets them in the entrance hall. He was one of Egypt’s most powerful rulers. Stairs lead to a stunning view of the Pyramids of Giza in the distance. And then there is the most mesmerizing sight of all. The entire contents of King Tut’s tomb are on display together for the first time (see “Tutmania Takes Off,” below).

The Grand Egyptian Museum officially opened this past fall. It took decades of planning. The complex holds more than 50,000 artifacts. It spans an area bigger than 90 football fields. It is the largest museum in the world dedicated to a single civilization.

But many Egyptians say the collection is not complete. Some of ancient Egypt’s most important artifacts are on display at museums in other countries. And those countries have no plans to return them. But the opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum has reignited the push to get them back.

“Their home should be the Grand Egyptian Museum,” says Zahi Hawass. He is the former head of Egypt’s antiquities program.

Ahmad Hasaballah/Getty Images

A 3,200-year-old statue of Ramses II welcomes visitors to the Grand Egyptian Museum.

Stolen Treasures?

How did many of Egypt’s treasures end up so far away? From the late 18th century to the mid-20th century, Great Britain and other European countries had a strong influence over Egypt. Their archaeologists traveled there in search of valuable objects from the past. European museums often helped pay for these efforts in order to build their collections.

The excavations turned up everything from ornate statues to detailed carvings that shed light on what Egypt was like thousands of years earlier. Some were removed from Egypt legally—through permits or a system called partage that let foreign archaeologists keep part of what they uncovered. Other treasures were stolen and taken to distant lands.

But the details surrounding how certain relics left Egypt are murky. That’s especially true for some of the most sought-after pieces.

How did many of Egypt’s treasures end up so far away? From the late 18th century to the mid-20th century, Great Britain and other European countries had a strong influence over Egypt. Their archaeologists traveled there in search of valuable objects from the past. European museums often helped pay for these efforts. They wanted to build their collections.

The excavations turned up everything from ornate statues to detailed carvings. They shed light on what Egypt was like thousands of years earlier. Some were removed from Egypt legally. That happened through permits or a system called partage. The system let foreign archaeologists keep part of what they uncovered. Other treasures were stolen and taken to distant lands.

But the details surrounding how certain relics left Egypt are murky. That is especially true for some of the most sought-after pieces.

The Grand Egyptian Museum is missing some of its country’s most prized artifacts.

The Rosetta Stone, for one, is claimed by both Egypt and England. It is one of the most important archaeological discoveries of all time because it helped unlock the mysteries of hieroglyphics, a type of ancient Egyptian writing. The stone slab is carved with the same passage in three writing styles. Comparing them helped experts decode hieroglyphics.

French soldiers uncovered the Rosetta Stone in 1799, a year after invading and seizing control of Egypt. Britain defeated the French in Egypt in 1801. Britain and France signed a treaty to formally end the fighting. Under the treaty, Britain got the Rosetta Stone and other Egyptian artifacts that France had claimed during its rule. The Rosetta Stone has been on display in the British Museum in London, England, since 1802.

But Egyptian officials say the treasure was not France’s to give away in the first place—and that it does not belong in London. “This is the icon of our Egyptian identity,” Hawass explains. “Is it the history of the English? No. It is the history of Egypt.”

For example, the Rosetta Stone is claimed by both Egypt and England. It is one of the most important archaeological discoveries of all time. It helped unlock the mysteries of hieroglyphics. That is a type of ancient Egyptian writing. The stone slab is carved with the same passage in three writing styles. Comparing them helped experts decode hieroglyphics.

French soldiers uncovered the Rosetta Stone in 1799. It was a year after they invaded and seized control of Egypt. Britain defeated the French in Egypt in 1801. Britain and France signed a treaty to formally end the fighting. Under the treaty, Britain got the Rosetta Stone and other Egyptian artifacts that France had claimed during its rule. The Rosetta Stone has been on display in the British Museum in London, England, since 1802.

But Egyptian officials say the treasure was not France’s to give away in the first place. And they say that it does not belong in London. “This is the icon of our Egyptian identity,” Hawass explains. “Is it the history of the English? No. It is the history of Egypt.”

About two decades after the Rosetta Stone was removed, another major relic was taken: the Dendera Zodiac. The Zodiac is an elaborate stone map of the sky. It proved that ancient Egyptians had an advanced understanding of astronomy. A French scholar found the Zodiac carved into the ceiling of an Egyptian temple in 1799. He and other scholars spent two decades studying it. In 1821, a French antiquities collector had workers remove the Zodiac using explosives. He sold the map to King Louis XVIII of France. It was eventually moved to the Louvre Museum in Paris, France, where it has been on display since 1922.

France says the collector had permission from Egypt to remove the Zodiac. But Egypt maintains that the collector and his workers were thieves.

It is a royal statue, however, that has stirred up the most controversy. The Neues Museum in Berlin, Germany, has the bust of Nefertiti—one of Egypt’s most famous works of art. Nefertiti was a powerful Egyptian queen who lived about 3,400 years ago.

About two decades after the Rosetta Stone was removed, the Dendera Zodiac was taken. That is another major relic. It is an elaborate stone map of the sky. It proved that ancient Egyptians had an advanced understanding of astronomy. A French scholar found the Zodiac carved into the ceiling of an Egyptian temple in 1799. He and other scholars spent two decades studying it. In 1821, a French antiquities collector had workers remove the Zodiac using explosives. He sold the map to King Louis XVIII of France. It was eventually moved to the Louvre Museum in Paris, France. It has been on display there since 1922.

France says the collector had permission from Egypt to remove the Zodiac. Egypt maintains that the collector and his workers were thieves.

But it is a royal statue that has caused the most controversy. The Neues Museum in Berlin, Germany, has the bust of Nefertiti. That is one of Egypt’s most famous works of art. Nefertiti was a powerful Egyptian queen who lived about 3,400 years ago.

Some officials say displaying Egyptian artifacts in museums around the world helps people learn about the civilization.

German archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt found the statue in a workshop in Egypt in 1912. He had permission to take some objects, but Egyptian officials claim the bust wasn’t one of them. They say he smuggled it out of the country. The Neues Museum, however, has argued Borchardt obtained the statue fairly.

For Egyptians, these prized treasures are a source of national and cultural pride. “These objects are of paramount importance to Egyptian society,” says Egyptologist Monica Hanna.

German archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt found the statue in a workshop in Egypt in 1912. He had permission to take some objects. Egyptian officials claim the bust was not one of them. They say he smuggled it out of the country. But the Neues Museum has argued he obtained the statue fairly.

For Egyptians, these prized treasures are a source of national and cultural pride. “These objects are of paramount importance to Egyptian society,” says Egyptologist Monica Hanna.

Tutmania Takes Off

Richard Nowitz/Getty Images (burial mask); Chronicle/Alamy Stock Photo (gas pump)

Left to right: King Tut’s burial mask is at the Grand Egyptian Museum; a gas pump in London, England, in the 1930s

In November 1922, British archaeologist Howard Carter made one of the greatest discoveries in history. He uncovered the long-lost tomb of the pharaoh Tutankhamen, now known as King Tut.

Royal tombs had been found before, but most were nearly empty—robbers had stripped them of their treasures. In contrast, Tut’s resting place teemed with gold and jewels. There were golden chariots, dazzling statues, jeweled chests, and more. No one in modern times had seen anything like it.

The discovery helped cement ancient Egypt’s place in history as a powerful civilization. Soon Tutmania gripped the world. Tut and ancient Egypt popped up in everything from fashion and music to architecture. In the decades since, some of Tut’s treasures have been showcased in traveling exhibitions. That has helped keep the civilization’s intrigue alive.

In November 1922, British archaeologist Howard Carter made one of the greatest discoveries in history. He uncovered the long-lost tomb of the pharaoh Tutankhamen, now known as King Tut.

Royal tombs had been found before, but most were nearly empty—robbers had stripped them of their treasures. In contrast, Tut’s resting place teemed with gold and jewels. There were golden chariots, dazzling statues, jeweled chests, and more. No one in modern times had seen anything like it.

The discovery helped cement ancient Egypt’s place in history as a powerful civilization. Soon Tutmania gripped the world. Tut and ancient Egypt popped up in everything from fashion and music to architecture. In the decades since, some of Tut’s treasures have been showcased in traveling exhibitions. That has helped keep the civilization’s intrigue alive.

History for All

Still, many people insist Egyptian artifacts should stay in their current museums, where some have been on display for more than 200 years.

Officials for those museums point out that they offer global access to the treasures, because so many people walk through their doors. Paris and London, for example, are two of the world’s most visited cities.

Another argument is that the relics get more attention in foreign museums than they would in their native country. The Rosetta Stone stands out at the British Museum because it is one of a kind there, officials say. But it might feel less unique in Egypt, which has 22 similar objects that helped experts understand hieroglyphics.

Plus, some museums say exposing visitors to ancient Egypt’s treasures helps spark a deeper interest in the civilization. Tourists who see the bust of Nefertiti in Germany, for example, may be inspired to travel to Egypt to learn more about her.

Salima Ikram, an Egyptologist, supports the return of the country’s key artifacts. However, she agrees that some of Egypt’s treasures should remain on display around the world. “These objects are our best ambassadors,” she says. “They inform, inspire, and delight people.”

Still, many people insist Egyptian artifacts should stay in their current museums. Some have been on display for more than 200 years.

Officials for those museums point out that they offer global access to the treasures. That is because so many people walk through their doors. Paris and London, for example, are two of the world’s most visited cities.

Another argument is that the relics get more attention in foreign museums than they would in their native country. Officials say the Rosetta Stone stands out at the British Museum because it is one of a kind there. But it might feel less unique in Egypt. There are 22 similar objects in Egypt that helped experts understand hieroglyphics.

Plus, some museums say exposing visitors to ancient Egypt’s treasures helps spark a deeper interest in the civilization. For example, tourists might see the bust of Nefertiti in Germany. Then they may be inspired to travel to Egypt to learn more about her.

Salima Ikram is an Egyptologist. She supports the return of the country’s key artifacts. But she agrees that some of Egypt’s treasures should remain on display around the world. “These objects are our best ambassadors,” she says. “They inform, inspire, and delight people.”

C 197 (Photo-Collection of Johann Georg von Sachsen, 1904-1930), Nr. 6643/University Archives of Freiburg (1912); Ulrich Baumgarten via Getty Images (Neues Museum)

Left to right: Men who helped find the bust of Nefertiti in 1912 cradle the statue at the discovery site; About half a million people visit the Nefertiti statue at the Neues Museum in Germany each year.

Making Progress

Egyptian officials have secured the return of about 30,000 relics over the past decade, including an elaborate gilded coffin in 2019 from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. And their recovery efforts are still underway.

This past fall, American authorities helped recover and return 36 Egyptian artifacts in the United States that had been illegally removed from Egypt. And officials in the Netherlands recently announced plans to return a valuable ancient stone bust. For many Egyptians, the progress is a hopeful sign.

Reclaiming these items helps make up for wrongs committed against Egypt more than two centuries ago, Hanna says. “We cannot change the past, but we can correct it.”

Egyptian officials have secured the return of about 30,000 relics over the past decade. That includes an elaborate gilded coffin in 2019 from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. And recovery efforts are still underway.

This past fall, American authorities helped recover and return 36 Egyptian artifacts in the United States. They had been illegally removed from Egypt. And officials in the Netherlands recently announced plans to return a valuable ancient stone bust. For many Egyptians, the progress is a hopeful sign.

Reclaiming these items helps make up for wrongs committed against Egypt more than two centuries ago, Hanna says. “We cannot change the past, but we can correct it.”

YOUR TURN

Dig Deeper

What makes an object from the past an important artifact? Talk to your classmates about why objects like the Rosetta Stone, the Dendera Zodiac, and the bust of Nefertiti are prized. Then consider: What objects from your daily life might be important enough to display in a museum hundreds of years from now? Why?

What makes an object from the past an important artifact? Talk to your classmates about why objects like the Rosetta Stone, the Dendera Zodiac, and the bust of Nefertiti are prized. Then consider: What objects from your daily life might be important enough to display in a museum hundreds of years from now? Why?

Interactive Quiz for this article

Click the Google Classroom button below to share the Know the News quiz with your class.

Download .PDF