Question: How has the way people use phones changed over time?

NCSS: Time, Continuity, and Change • Science, Technology, and Society

Common Core: R.3, R.7

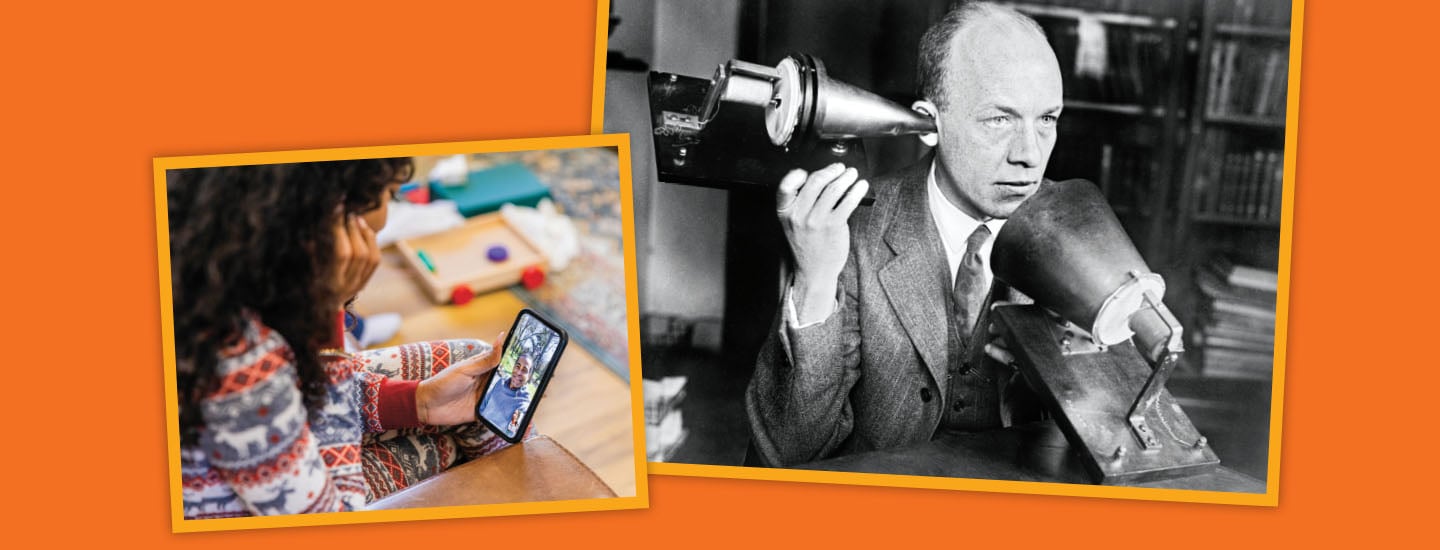

Left: Cell phones debuted nearly 100 years after the first phone. Right: Can you hear me now? A man demonstrates Bell’s first telephone.

SDI Productions/Getty Images (cell phone); IanDagnall Computing/Alamy Stock Photo (first telephone)

STANDARDS

NCSS: Time, Continuity, and Change • Science, Technology, and Society

Common Core: R.3, R.7

U.S. HISTORY | TECHNOLOGY

How Phones Changed the World

Alexander Graham Bell made the first phone call 150 years ago. Since then, phones have transformed dramatically—and transformed us in the process.

Question: How has the way people use phones changed over time?

On March 10, 1876, a young inventor in Massachusetts named Alexander Graham Bell leaned over a funny-looking device made of wood, wires, and a metal cone. He took a deep breath and then spoke into it: “Mr. Watson, come here. I want to see you.”

In another room, Bell’s assistant Thomas Watson heard the words come through a receiver. They were staticky and hard to understand, but they got through.

It was the very first phone call in history—and it changed the world. Since then, the telephone has evolved from a clunky communication tool to a portable do-everything device. And in the process, it has transformed us too.

“The telephone changed how Americans interacted,” says Josh Lauer, a communications professor at the University of New Hampshire. “It introduced us to a belief that social interactions should be convenient and instant.”

Faster Communication

You might think nothing of texting a friend about homework or hopping on a video call with a relative in another state—or even another country. But before the telephone, staying in touch took a lot more effort. “The only way to talk to someone was to visit them in person,” Lauer explains.

You could also mail a letter, but getting a response could take days, weeks, or longer. (Talk about snail mail!) The only faster option was the telegraph, a device developed in the 1830s. It transmitted short messages using dots and dashes that stood for letters. To send a message, however, you would most likely have to go to a telegraph office. And hearing back could take hours or even days.

The invention of the telephone sped things up—a lot. A few months after that first call, Bell showed that his invention could connect callers instantly, even if they were miles apart. It was a game-changer. Distant relatives could stay in touch more frequently, businesses could grow more easily, and news could spread faster and farther than ever before.

Still, early telephones were nothing like the ones we use today. For one thing, you needed two phone lines: one to talk into and one to listen on. And you couldn’t ring up more than one place. Each phone was connected by a wire to just one other phone, and that was the only one it could reach.

Camerique/Getty Images

Switchboard operators connect calls. Almost all operators were women.

Calling Gets Easier

That one-phone limit didn’t last long though. In 1878, an invention called a switchboard made it possible to call multiple people from a single phone. Staffed by telephone operators, a switchboard was a big panel covered with holes and wires. Each hole was linked to a different phone line. To make a call, you would tell the operator who you wanted to reach, and the operator would plug in a cord to connect your phone line to theirs.

That advancement made phones even more popular. By 1880, there were about 50,000 telephones in the United States—mostly in businesses and the homes of wealthy people. Families without a phone could go to a local store to make a call. No conversation was private though, even at home. Switchboard operators could listen in!

As more people and businesses got phones, meeting in person became optional for many tasks. Before then, for example, people had to mail a letter or go to the doctor’s office in person to make an appointment. Now they could call from home—in pajamas! They could also ring up stores to place orders.

Phones started changing the way Americans socialized too—but not everyone liked it. Instead of mailing out invitations for a get-together, for instance, people could invite friends by phone. Critics said it was rude because it put people on the spot to give an answer right away.

Connecting the World

There were almost 6 million phones in the U.S. by 1910. Crews strung miles of copper wire to link phones in distant places. In 1915, the first coast-to-coast call was made from New York to California. Twelve years later, the first international phone call was made, from the U.S. to England.

By the 1960s, Americans owned more than 80 million phones. And users could call people directly, no switchboard operator needed.

As the decades passed, phones became an even bigger part of daily life. Teens spent hours talking to their friends. But most homes had just one phone. So if a parent needed to make a call, you had to hang up. And privacy was still in short supply. Phones were usually in a central spot, like the kitchen, and you could take the receiver only as far as the cord would stretch—sometimes just a few feet.

Talking On the Go

Home phones had another drawback. What if you were at the mall and wanted your friends to meet you? To call on the go, you had to use a pay phone.

These public phones could be found in places like stores or in phone booths on sidewalks. Putting a coin in the phone would pay for a call lasting a few minutes. But if you wanted to phone a friend and they weren’t home, you were out of luck.

Inventors, meanwhile, were hard at work creating a type of phone that would let people make or receive calls from just about anywhere. They envisioned phone signals carried by radio towers rather than wire so that callers could talk on the go.

In 1973, an American named Martin Cooper made the world’s first cell phone call on a sidewalk in New York City. The phone was plain by today’s standards, and it weighed more than 2 pounds. But it proved that wireless calling was possible.

It was another 10 years before the first cell phones went on sale. They were expensive—up to nearly $13,000 in today’s dollars!

Inventing the Telephone

Alexander Graham Bell Family Papers at the Library of Congress

Bell sketched this in 1876 to show how his phone would work.

Universal History Archive/Getty Images

Alexander Graham Bell as a young man

Alexander Graham Bell is often credited with creating the phone because he received the first telephone patent, on March 7, 1876. A patent gives someone exclusive rights to an invention. But Bell wasn’t the only one to dream up the device.

Some historians credit Antonio Meucci with inventing the phone. The Italian immigrant started working on a talking telegraph as early as 1849. He began the patent process in 1871 but ran out of money to pay for it.

Meanwhile, German teacher Johann Philipp Reis built a phone in 1861. His device transmitted speech but not back-and-forth conversation. Reis did not patent his work.

American inventor Elisha Gray built a device similar to Bell’s. Gray filed with the patent office on February 14, 1876—but he was too late. Bell had filed a few hours earlier. Talk about a close call!

Phones Get Smarter

As cell phones got smaller and cheaper, they became more common. The devices offered convenience, Lauer explains. “People could communicate on the go. You could make plans on the fly and make adjustments if you were running late.”

The invention of text messaging in the early 1990s took that convenience to a new level. People could stay in touch constantly without having to say a word. Texting did take effort though. Many phones only had number buttons, each labeled with a few letters. You had to press each button one, two, or three times to get the right letter to pop up.

In 2002, a device called the BlackBerry 5810 went on sale. It could connect to the internet—a relatively new invention itself. That meant people could get emails and look up information on the go. It also had a tiny keyboard.

Then, in 2007, Apple introduced the iPhone. It combined a phone, a camera, a music player, and the internet all in one device. Dubbed a smartphone, it revolutionized people’s daily lives.

Do-Everything Devices

Almost all American adults now own a cell phone. But the devices are unlike anything that Bell likely imagined when he made that first call. “Smartphones, in many ways, are not even phones anymore,” Lauer says. “They are computers, cameras, televisions, music players, and video game consoles.”

What will telephones be able to do in the next 150 years? Only time will tell.

YOUR TURN

Imagine a Phone of the Future

What will be the next big development in phones? Sketch your idea for a phone of the future, and write a short explanation about how it would work. Then consider: How would your invention change communication?