Question: How does this teen’s story help you understand the U.S. civil rights movement?

NCSS: Time, Continuity, and Change • Individual Development and Identity

Common Core: R.2, R.7

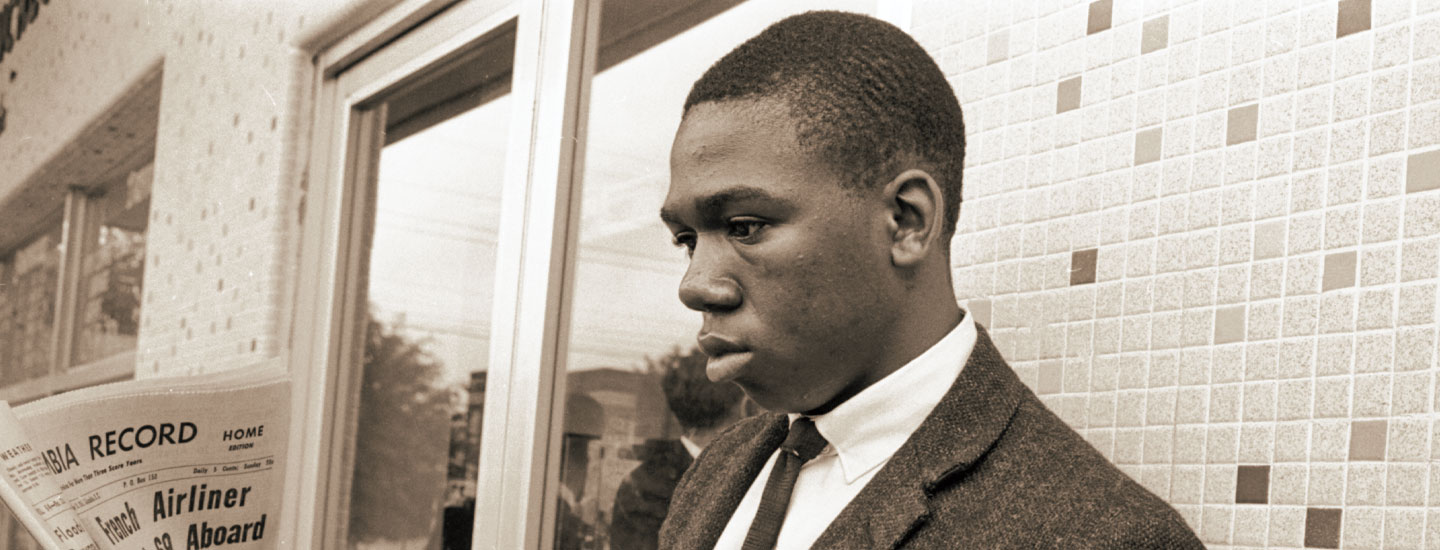

Charles Person, 18, took part in the first Freedom Ride, in May 1961.

Copyright © The State Media Company via Family History Center at Richland Library/PARS International Corp.

STANDARDS

NCSS: Time, Continuity, and Change • Individual Development and Identity

Common Core: R.2, R.7

U.S. HISTORY

True Teens of History

The Youngest Freedom Rider

Charles Person, 18, protested segregation on interstate bus travel in 1961. His actions helped change the United States.

Question: How does this teen’s story help you understand the U.S. civil rights movement?

Charles Person knew he was in trouble. It was May 14, 1961, and the 18-year-old was standing outside the Greyhound bus terminal in Birmingham, Alabama. The station was segregated, with separate areas for White and Black riders. Charles, a Black college student, was about to walk into a Whites only area. Inside, a mob of White men was waiting for him.

Charles was part of a group called the Freedom Riders. The 13 activists were riding public buses from Washington, D.C., to New Orleans, Louisiana, to challenge segregation. At every stop, the men and women protested peacefully by going into Whites only restaurants and restrooms in the stations. They often encountered violence. But in Birmingham, Charles and the others would endure an attack so brutal that it would draw national attention to their cause.

The U.S. Supreme Court had already declared in several cases that segregation was unconstitutional, including in interstate bus terminals. Yet many bus stations in the South remained separated by race.

The goal of the Freedom Riders was to get the U.S. government to enforce the Court rulings against segregation. They hoped their actions would help end discrimination across the country.

That’s what Charles, the youngest Freedom Rider, had on his mind that day 65 years ago. As he and the other protesters entered the bus terminal, the mob advanced. With his head held high, Charles stepped forward.

AP Images

A police officer at a bus terminal in McComb, Mississippi, in 1961

Growing Up in the South

Charles was born on September 27, 1942, in Atlanta, Georgia. His father was a hospital attendant, and his mother worked in the home of a White family.

Nearly 75 years had passed since the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guaranteed equal rights to Black Americans. But much of the nation remained unequal. Many state and local governments enforced restrictive practices known as Jim Crow laws.

In many towns and cities, Black people could not live in certain neighborhoods. They could not drink from the same water fountains or go to the same schools as White people. They were also targets for violence at the hands of White extremists.

Still, Charles’s mother told him that he could be anything he wanted to be. In 1960, Charles graduated from high school with honors.

Hoping to become a physicist, he applied to the Georgia Institute of Technology, a top university for that field. But the school did not accept Black students, so he was rejected.

Recruiting Freedom Riders

This advertisement calling for people to join a bus protest caught Charles Person’s eye in March 1961. It had been cut out of a national student newspaper and posted on a bulletin board at a church near his college in Atlanta, Georgia.

The Student Voice via Civil Rights Movement Archive

Struggling for Equality

Charles enrolled at Morehouse College, a Black university in Atlanta, instead. But he still felt the sting of rejection. Around the same time, some college students were taking a stand for civil rights. Charles joined the Atlanta Student Movement, a group that organized nonviolent demonstrations.

One of Charles’s first protests with the group landed him behind bars. In February 1961, he was jailed for 16 days for taking part in a sit-in at a Whites only lunch counter in Atlanta. Shortly after his release, he learned about an opportunity to take part in a “Freedom Ride” (see “Recruiting Freedom Riders,” above).

The Freedom Rides were created by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), a civil rights group that organized anti-segregation efforts. CORE leaders were seeking people to travel by bus through the South in an attempt to end racial separation in bus stations.

The Birmingham News/AP Images

Charles Person (standing, left), with other Freedom Riders in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1961

The Ride Begins

After seeing the ad, Charles knew that he wanted to join the Freedom Rides. The teen applied and was accepted, along with six other Black activists, including civil rights leader John Lewis.

The group also included six White activists. That was part of CORE’s strategy, historians say. The organization’s founders believed that people of all races had to work together to challenge segregation and other types of discrimination. Having Black riders alongside White ones also demonstrated that the civil rights movement was unified and diverse.

“They showed that the struggle for equality wasn’t just a Black problem,” says Ann Bausum, who wrote a book about the Freedom Rides. “It was an American problem.”

CORE trained the Freedom Riders to stay calm—even if they were attacked—rather than respond with violence. Then the protesters boarded two buses on May 4 and set off from Washington, D.C. Their first stop in Fredericksburg, Virginia, was uneventful. But in Charlotte, North Carolina, Charles was almost arrested for trying to have his shoes shined in a Whites only section of a bus terminal. And in Rock Hill, South Carolina, Lewis and other Freedom Riders were attacked by White men.

The protesters were met with more violence when they arrived in Alabama on May 14. Outside the city of Anniston, White extremists set one bus on fire. The Freedom Riders fled the flames, only to be beaten.

Later that same day, the bus Charles was on reached Birmingham. As he and other Freedom Riders walked into the bus terminal’s Whites only waiting area, a mob of White men engulfed them. Charles was hit in the head with a lead pipe. The assault left a fist-sized knot on the back of his neck that remained until he had it surgically removed 35 years later.

The Freedom Riders escaped only when a flashbulb went off. A news photographer had taken a photo of the assault. “It startled them,” Charles recalled in 2021, at age 78. “At that point, they just released me.”

Newspapers around the globe published photos of that day’s violence. President John F. Kennedy, who supported civil rights, saw the images and knew he had to do something.

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

People evacuate the bus that was set on fire in Anniston, Alabama, in 1961.

A Historic Change

While Kennedy considered a course of action, many of the Freedom Riders were too badly hurt to continue their journey by bus. The group flew to its final destination of New Orleans the next day.

The Freedom Riders’ trip was over, but their impact was just beginning. Inspired by their bravery, other people took up the cause, insisting that violence couldn’t win.

Within a few days, college students from Tennessee boarded buses heading south to do their own Freedom Ride. They too would face beatings and arrests.

Still, new groups of Freedom Riders from all over the nation continued to board buses throughout the summer. At one point, more than 300 of the protesters were jailed.

With tensions rising, the Kennedy administration reached out to the Interstate Commerce Commission, then a government agency that regulated railroads and interstate bus lines. The commission responded by declaring an end to segregation on interstate buses and in bus terminals. Beginning on November 1, 1961, Whites only signs in bus terminals were taken down.

Though it was a historic victory for the Freedom Riders, the push for civil rights was not over. Three more years of marches and other demonstrations achieved another major milestone. The U.S. Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The law outlawed segregation in public places nationwide.

Ted Polumbaum/Newseum Collection

Volunteers register people to vote in Mississippi in 1964.

Their Path to Change

Many civil rights activists, including the Freedom Riders, believed nonviolence was the best way to achieve equality. Here are three common strategies they used.

Voter Registration: In the early 1960s, many Black Americans in the South were prevented from voting. Activists helped them register to vote, giving them a say in the government.

Boycotts: Protesters refused to use services or buy goods from businesses that did not treat Black people and White people the same. This put a financial strain on businesses.

Marches: Demonstrators took part in marches, some of which drew hundreds of thousands of people. Such events helped pressure lawmakers to act on civil rights issues.

Lasting Voice for Equality

Charles had returned home in 1961. He knew he wanted to continue serving his country, as he believed he had done by participating in the Freedom Rides. With his parents’ support, he enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps.

He served in the military for 20 years, including two years in the Vietnam War (1954-1975). After retiring, he started an electronics business in Atlanta. He also married and raised five children.

All the while, Charles continued to advocate for equality. In 2021, he co-founded the Freedom Riders Training Academy. The organization teaches young people how to protest peacefully. That same year, he wrote a memoir about his time as a Freedom Rider. Charles also spoke publicly about his experiences as a teen in the civil rights movement up until his death in 2025 at age 82.

“Change usually begins with young people because they are impatient, and they are not going to accept anything else but change—especially when they know things are wrong,” Charles said in 2021. “You have the ability to change the world, and it begins with one person.”

YOUR TURN

Write a Journal Entry

Pick one sentence or idea from the article that stands out to you. How does your selection help you understand the U.S. civil rights movement? Write a journal entry explaining what the sentence or idea means to you.