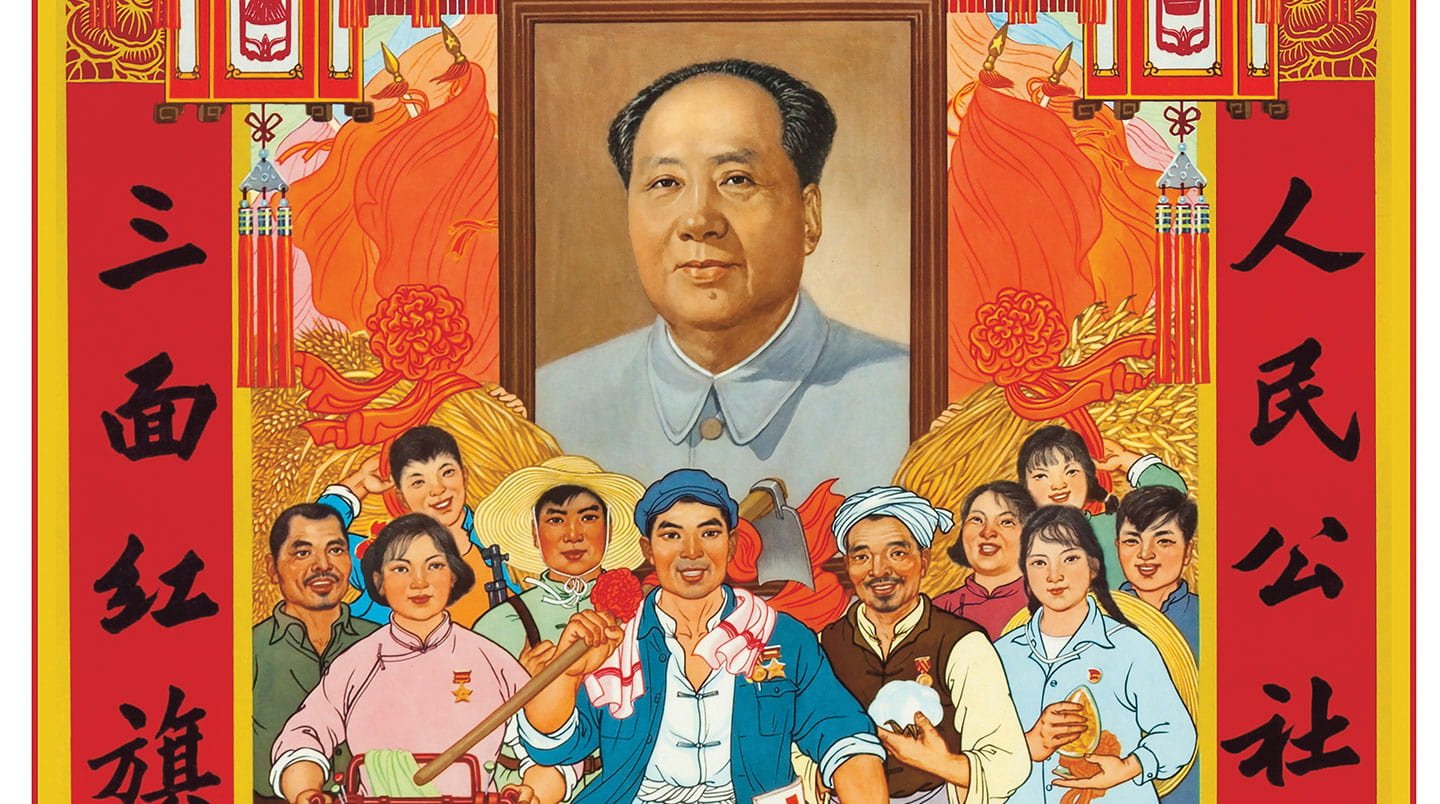

In the spring of 1966, the future was looking bleak for the People’s Republic of China—and for its leader, Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong.

Just 17 years earlier, Mao had led his followers to victory in a long and bloody civil war, then had proudly established China as a Communist nation. (China was the first major Asian country to choose Communist rule.) Mao’s actions made him a hugely popular national hero.

But his attempts to reform the nation’s economy to reflect his Communist ideals failed miserably. The Great Leap Forward, a plan he launched in 1958, had eliminated private ownership of land and banned family farming. Instead, all farmwork was done by people the government organized into living and working units called communes. All decisions about what crops to grow, and when and how much, were decided by government officials often far removed from the actual farms.

It was a disaster. Instead of producing a bounty of crops to feed the nation, the Great Leap Forward contributed to a series of terrible famines. From 1959 to 1962, an estimated 45 million Chinese citizens died. Starvation left millions of others with long-lasting damage to their physical and mental health.