When Violet Harris, a 15-year-old in Seattle, Washington, learned that officials were closing schools to stop the spread of a deadly disease, she responded like many students: with excitement.

“It was announced in the papers tonight that all churches, shows, and schools would be closed until further notice, to prevent Spanish influenza from spreading,” she wrote in her diary on October 5, 1918. “Good idea? I’ll say it is! So will every other school kid.”

But her initial thrill didn’t last. As the flu spread through her community, Violet began to worry, especially when her best friend, Rena, became infected. “I stayed in all day and didn’t even go to Rena’s,” Violet wrote weeks later. “The flu seems to be spreading. And Mama doesn’t want us to go around more than we need to.”

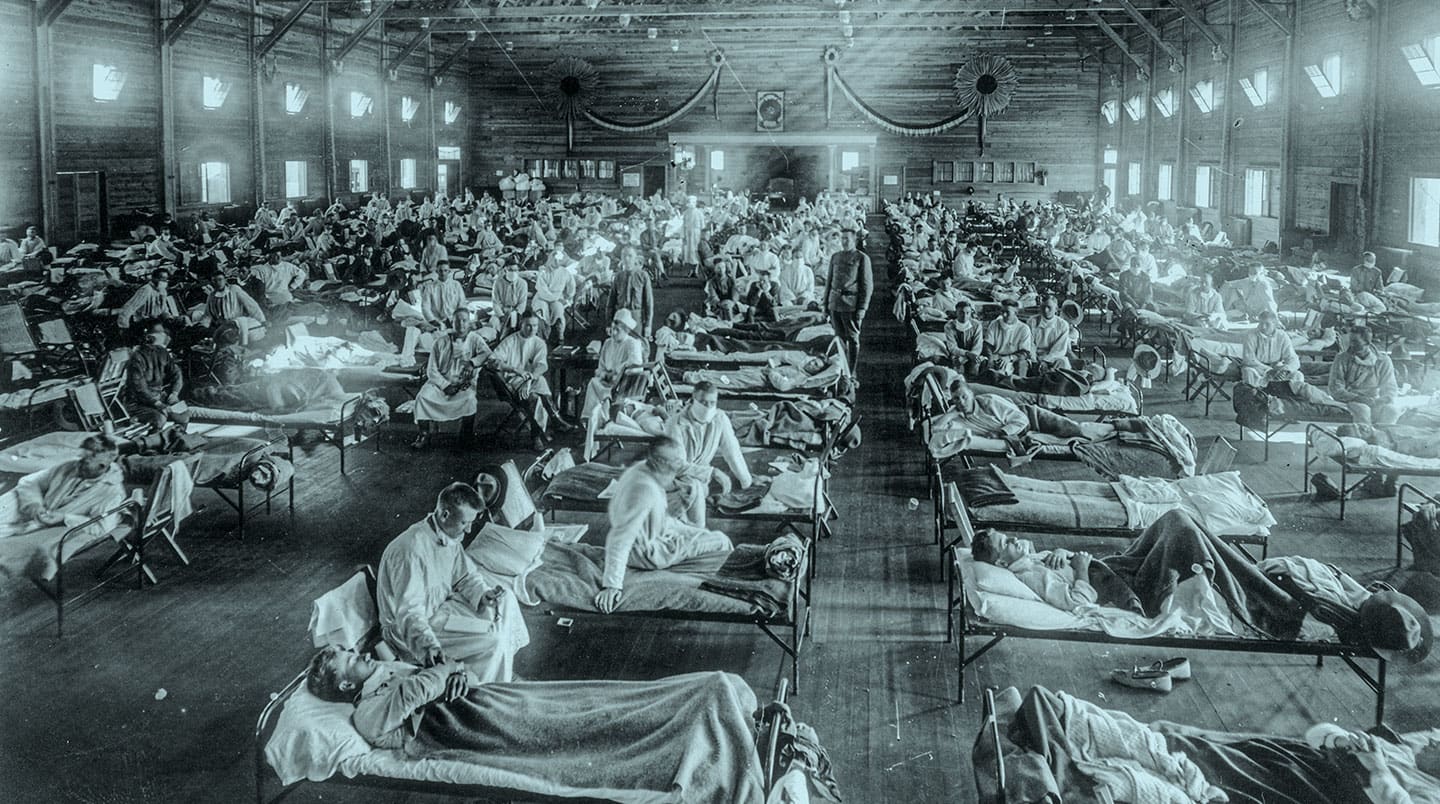

If her experience sounds familiar, that’s because Violet lived through a pandemic too. More than 100 years before Covid-19, the world was gripped by a disease known as Spanish influenza or the Spanish flu.

Experts estimate that by the time that flu subsided in 1919, one in every three people worldwide had been infected and at least 50 million had died. Though far fewer people have died from Covid-19, many historians see similarities between the two pandemics. Just as today, officials back then had to make difficult decisions about closing schools and implementing social distancing.

“I’m often struck by how ancient this [current] pandemic feels,” says Laura Spinney. She’s the author of Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World. “We don’t have a vaccine yet, so the only way we can slow the spread of the disease is to use these social distancing measures, and they are not new. They were used in 1918.”

Violet Harris was a 15-year-old living in Seattle, Washington. When she learned that officials were closing schools to stop the spread of a deadly disease, she responded like many students: She was excited.

“It was announced in the papers tonight that all churches, shows, and schools would be closed until further notice, to prevent Spanish influenza from spreading.” That is what Violet wrote in her diary on October 5, 1918. “Good idea? I’ll say it is! So will every other school kid.”

But her initial thrill did not last. The flu spread through her community. Violet began to worry, especially when her best friend, Rena, became infected. “I stayed in all day and didn’t even go to Rena’s,” Violet wrote weeks later. “The flu seems to be spreading. And Mama doesn’t want us to go around more than we need to.”

If her experience sounds familiar, that is because Violet lived through a pandemic too. More than 100 years before Covid-19, the world was gripped by a disease known as Spanish influenza or the Spanish flu.

Experts estimate that by the time that flu let up in 1919, one in every three people worldwide had been infected. At least 50 million people had died. Far fewer people have died from Covid-19. But many historians still see similarities between the two pandemics. Back then, officials had to make the same difficult decisions being made today. They had to decide about closing schools and implementing social distancing.

“I’m often struck by how ancient this [current] pandemic feels,” says Laura Spinney. She is the author of Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World. “We don’t have a vaccine yet, so the only way we can slow the spread of the disease is to use these social distancing measures, and they are not new. They were used in 1918.”