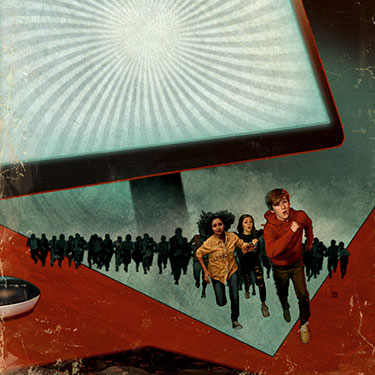

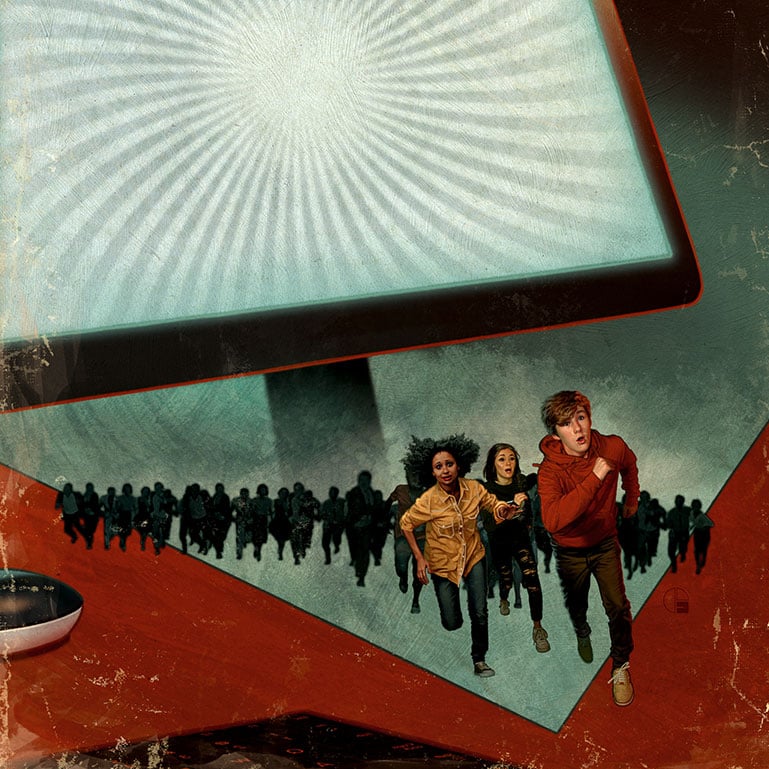

You’re scrolling through your Twitter feed when all of a sudden, a shocking headline fills your screen: “England BANS VIDEO GAMES!!” Outraged, you text your friends, who in turn text their friends. Could the United States be next, you wonder?

Soon, millions of people across the country are sharing the article on Facebook and Twitter. Within hours, the story has gone viral. The only problem? The article is fake—and you fell for it.

Made-up stories like that one are designed to look real but are completely or partly untrue. Sometimes it’s easy to tell when an article is false—words might be misspelled or randomly capitalized, or the headline might contain multiple exclamation points. But more often than not, fake-news writers are careful to make their stories seem real by including headlines, details, and data that sound believable.

You are scrolling through your Twitter feed. All of a sudden, a shocking headline fills your screen. “England BANS VIDEO GAMES!!” Outraged, you text your friends. They in turn text their friends. Could the United States be next, you wonder?

Soon, millions of people across the country are sharing the article on Facebook and Twitter. Within hours, the story has gone viral. The only problem? The article is fake—and you fell for it.

Made-up stories like that one are designed to look real but are completely or partly untrue. Sometimes it is easy to tell when an article is false. Words might be misspelled or randomly capitalized. The headline might contain multiple exclamation points. But fake-news writers are usually careful to make their stories seem real. They include headlines, details, and data that sound believable.