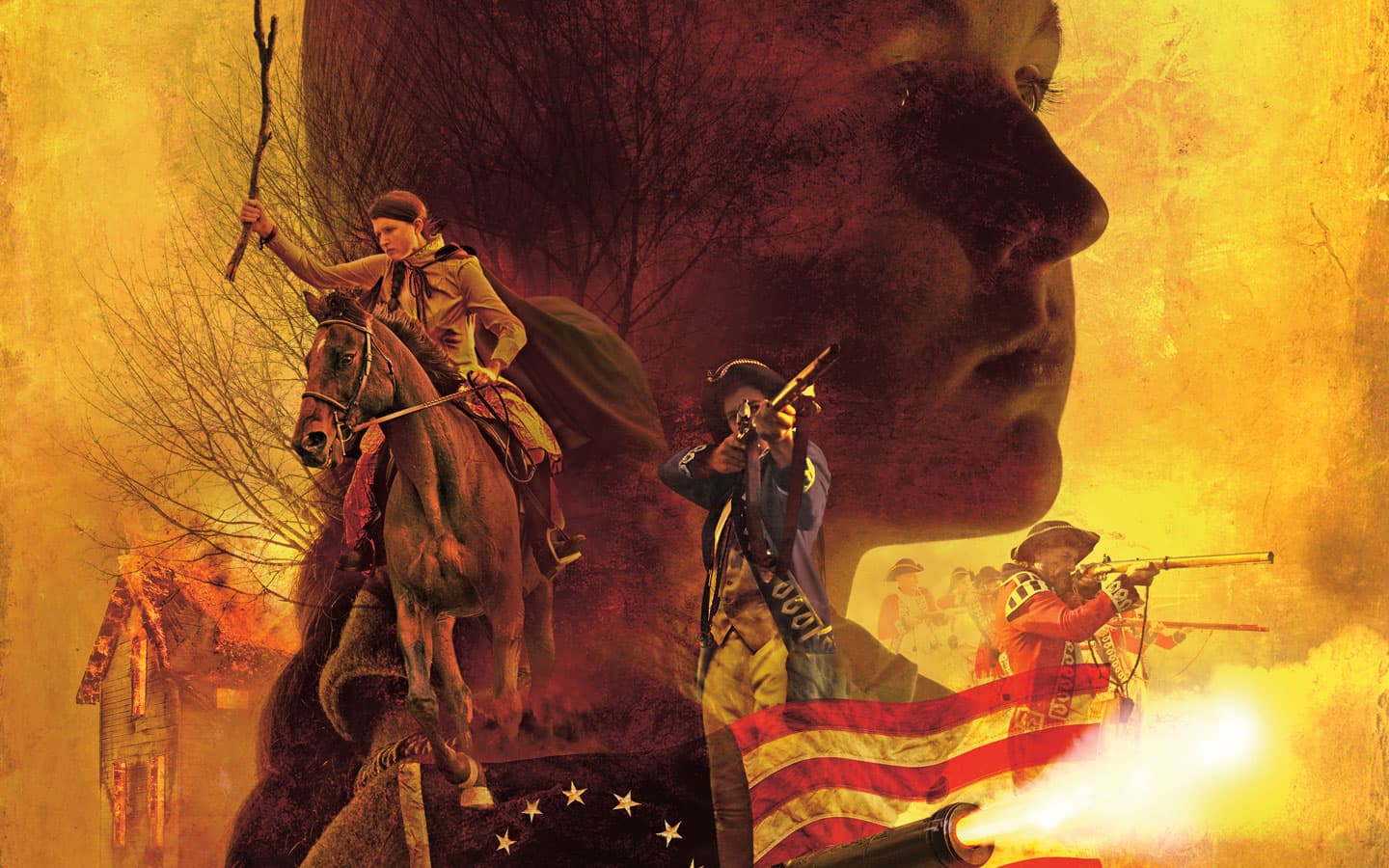

For the first time in her 16 years, Sybil Ludington felt as if the whole world rested on her shoulders. Not an hour earlier, she had been safe in her home in Fredericksburg, New York, with her parents and siblings. Now she was racing on horseback in the dead of night for the lives of her family, her village, and her fellow Patriots, who were fighting a brutal war for independence from Great Britain.

The first sign of the emergency had been a sudden pounding at the door late that evening in April 1777. It was a messenger. British troops were destroying the nearby town of Danbury, he cried breathlessly.

Located just 12 miles away in Connecticut, Danbury was a key supply base for the American colonists who formed the Continental Army. Earlier that afternoon, about 2,000 British troops had invaded the town.

The soldiers had lugged thousands of pounds of goods belonging to the American army into the street and set them on fire. Countless barrels of beef, flour, and corn went up in flames—along with about 1,000 tents. The troops then went wild, torching houses and forcing the residents to flee.

The messenger had ridden several hours from Danbury to reach Sybil’s father, Colonel Henry Ludington. He was the leader of a local militia of farmers and laborers. Now his forces were needed to fight off the British, the messenger said. But the colonel’s men were spread over many miles. Someone would have to ride into the night and gather them.

For the first time in her 16 years, Sybil Ludington felt as if the whole world rested on her shoulders. Not an hour earlier, she had been safe in her home in Fredericksburg, New York. She had been with her parents and siblings. Now she was racing on horseback in the dead of night. Sybil was fighting for the lives of her family, her village, and her fellow Patriots. They were in a brutal war for independence from Great Britain.

The first sign of the emergency had been a sudden pounding at the door late that evening in April 1777. It was a messenger. “British troops are destroying the nearby town of Danbury!” he cried breathlessly.

Danbury was located just 12 miles away in Connecticut. It was a key supply base for the American colonists who formed the Continental Army. Earlier that afternoon, about 2,000 British troops had invaded the town.

The soldiers had carried thousands of pounds of goods belonging to the American army into the street. They set them on fire. Countless barrels of beef, flour, and corn went up in flames. So did about 1,000 tents. The British troops then went wild. They torched houses, forcing the residents to flee.

The messenger had ridden several hours from Danbury to reach Sybil’s father. Her father’s name was Colonel Henry Ludington. He was the leader of a local militia of farmers and laborers. The messenger said his forces were now needed to fight off the British. But the colonel’s men were spread over many miles. Someone would have to ride into the night and gather them.