Courtesy of Joan Johns Cobbs

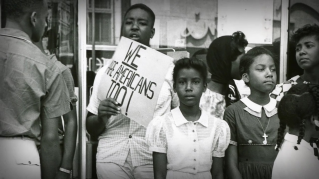

Behind a deep-purple curtain on the stage of her school’s auditorium, Barbara Johns, 16, stood waiting. What she was about to do could put her—and her friends and family—in danger. But she wasn’t afraid. The curtain rose. A gasp rippled across the room as hundreds of students—expecting to see their principal—looked up at her with surprise.

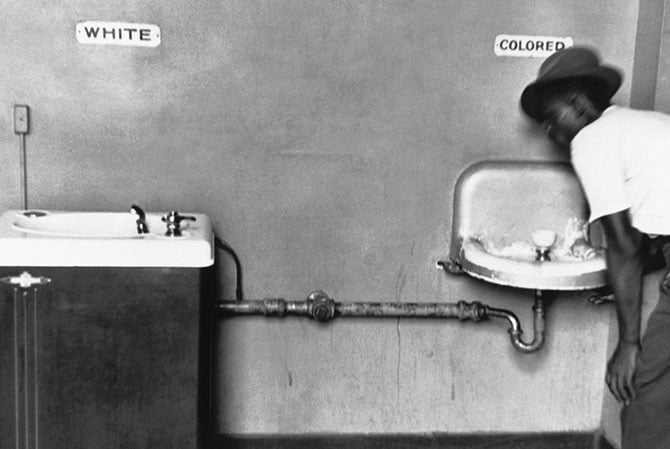

It was the spring of 1951 in the rural community of Farmville, Virginia. At the time, African Americans like Barbara were often treated with hatred and

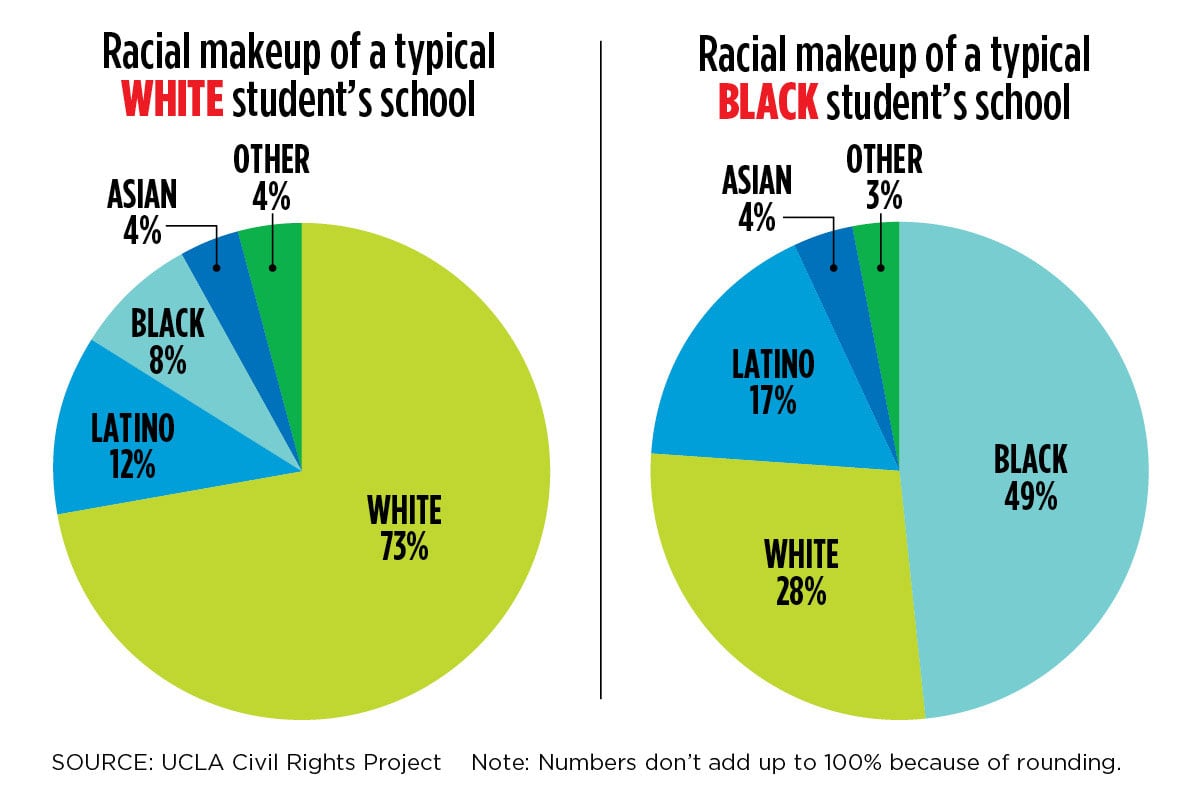

In Virginia—and 20 other states—Black students and white students were also required to attend

Barbara’s school, the all-Black Robert Russa Moton High School, for example, was literally falling apart. The ceilings were so cracked that Barbara and her classmates had to use umbrellas indoors when it rained. The toilets barely worked, and the one-story building had no gym, cafeteria, or science lab.

The school was also severely overcrowded. It was built to hold 180 students, yet 450 were enrolled there. To create more space, some classes were held in a run-down bus in the parking lot or in shacks in the schoolyard made of wood and paper.

Meanwhile, the all-white Farmville High School just minutes from Moton had spacious classrooms, modern heating, and a real cafeteria.

When Moton parents and teachers complained to the school board, they were told that a new school would be built soon. It was clear, though, that “soon” would probably never come.