Jim McMahon/Mapman®

“I can never put on paper the thrill of that underground ride to Harlem.” So wrote poet Langston Hughes about a day in 1921 when the then 19-year-old African American, originally from Missouri, got on a New York City subway train for the first time and rode uptown to Harlem.

“I went up the steps and out into the bright September sunlight,” Hughes wrote. “Harlem! I stood there, dropped my bags, took a deep breath, and felt happy again.”

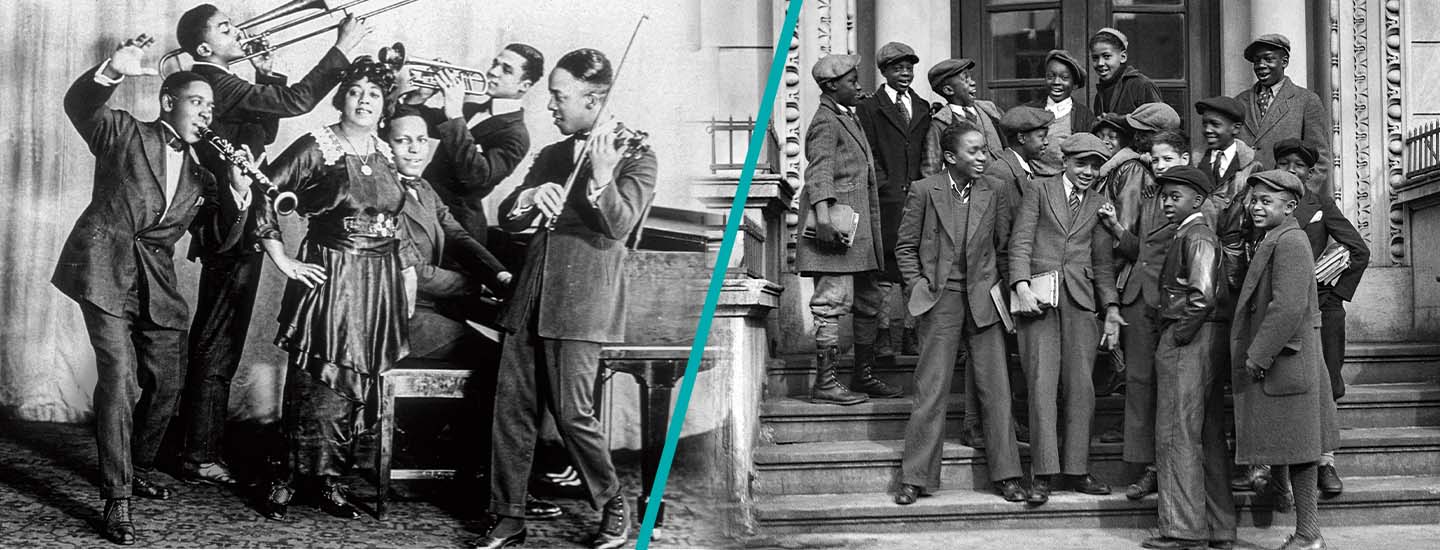

Amazing things were happening in Harlem. In just a few years, it had been transformed from a sleepy section of upper Manhattan into what was being called the capital of Black America. Its residents had formed a community where they were making music, literature, and art that was their own—and uniquely American. Harlem was the place for an ambitious young Black creator to be.

What was special about Harlem? For many generations, it was considered the countryside, a place where wealthy New Yorkers owned estates. By the late 19th century, immigrants from Germany, Ireland, and other European countries had also settled in the 1.5-square-mile area. Sensing opportunity, real estate developers built many houses and apartment buildings there. They were hoping to lure middle-class White families into a freshly created neighborhood.

Instead, Harlem became a magnet for African Americans. Black New Yorkers from other parts of the city went there to escape discrimination and overcrowding. Many people also arrived from Southern states during what became known as the Great Migration. That was when millions of Black Southerners, fleeing racial violence and segregation, relocated to cities in the North and Midwest to seek economic and educational opportunities. Black immigrants from Jamaica and other Caribbean countries came to Harlem too, making the area even more diverse.

By the early 1920s, Harlem was home to the country’s highest concentration of Black people. In its cafés, churches, and homes, in theaters and on the streets, some of the era’s most talented musicians, writers, and artists found inspiration—and the freedom to express themselves. The result was a new cultural identity for Black Americans. It would come to be known as a renaissance, or rebirth. And thanks to new means of communication—including radio, records, and movies—its influence would extend far beyond the city blocks where it began, notes John Reddick. He’s a Harlem historian and scholar at Columbia University in New York City.

The Harlem Renaissance, Reddick says, “crossed all boundaries, to both Black and White Americans, and to an international audience.” Read on to experience some of the magic of Harlem for yourself!

“I can never put on paper the thrill of that underground ride to Harlem.” So wrote poet Langston Hughes about a day in 1921 when the young African American from Missouri, age 19, first took a New York City subway train. He rode it uptown to Harlem.

“I went up the steps and out into the bright September sunlight,” Hughes wrote. “Harlem! I stood there, dropped my bags, took a deep breath, and felt happy again.”

Amazing things were happening in Harlem. In just a few years, it had been changed from a sleepy section of upper Manhattan into what was being called the capital of Black America. Its residents had formed a community. They were making music, literature, and art that was their own—and uniquely American. Harlem was the place for an ambitious young Black creator to be.

What was special about Harlem? For many generations, it was considered the countryside, a place where wealthy New Yorkers owned estates. By the late 19th century, immigrants from Germany, Ireland, and other European countries had also settled in the 1.5-square-mile area. Sensing opportunity, real estate developers built many houses and apartment buildings there. They were hoping to draw middle-class White families into a freshly created neighborhood.

Instead, Harlem became a magnet for African Americans. Black New Yorkers from other parts of the city went there to escape discrimination and overcrowding. Many people also arrived from Southern states during what became known as the Great Migration. That was when millions of Black Southerners fled racial violence and segregation. They moved to cities in the North and Midwest to find economic and educational opportunities. Black immigrants from Jamaica and other Caribbean countries went to Harlem too, making the area even more diverse.

By the early 1920s, Harlem was home to the country’s highest concentration of Black people. In its cafés, churches, and homes, in theaters and on the streets, some of that time’s most talented musicians, writers, and artists found inspiration and the freedom to express themselves. The result was a new cultural identity for Black Americans. It would come to be known as a renaissance, or rebirth. And thanks to new means of communication, including radio, records, and movies, its influence would extend far beyond the city blocks where it began, notes John Reddick. He is a Harlem historian and scholar at Columbia University in New York City.

The Harlem Renaissance, Reddick says, “crossed all boundaries, to both Black and White Americans, and to an international audience.” Read on to experience some of the magic of Harlem for yourself!