For Britain, the acts of destruction were the last straw. Beginning in March 1774, Parliament passed laws known as the Coercive Acts to punish the Colonies, particularly Boston.

The first law closed Boston Harbor until the town paid for the destroyed tea—valued at about $1.5 million today. With ships unable to pass in or out, many local businesses were devastated. Another Coercive Act required colonists to house British soldiers in their towns.

Parliament’s crackdown only inflamed resistance. In September 1774, representatives from 12 of the 13 Colonies met in Philadelphia. The gathering, now known as the First Continental Congress, formally demanded that the Coercive Acts be ended. Parliament refused.

But as the divide with Britain grew, the relationship between the Colonies deepened. The acts of rebellion “helped to unite the Colonies for war and independence,” says historian Benjamin Carp. It was exactly what Adams had hoped for.

Virginia delegate Patrick Henry made that plain at the Continental Congress. “The distinctions between Virginians, Pennsylvanians, New Yorkers, and New Englanders are no more,” he said. “I am not a Virginian, but an American.”

Within months, the Americans and the British were at war. When the American Revolution ended eight years later, the Colonies formed a new nation, the United States of America.

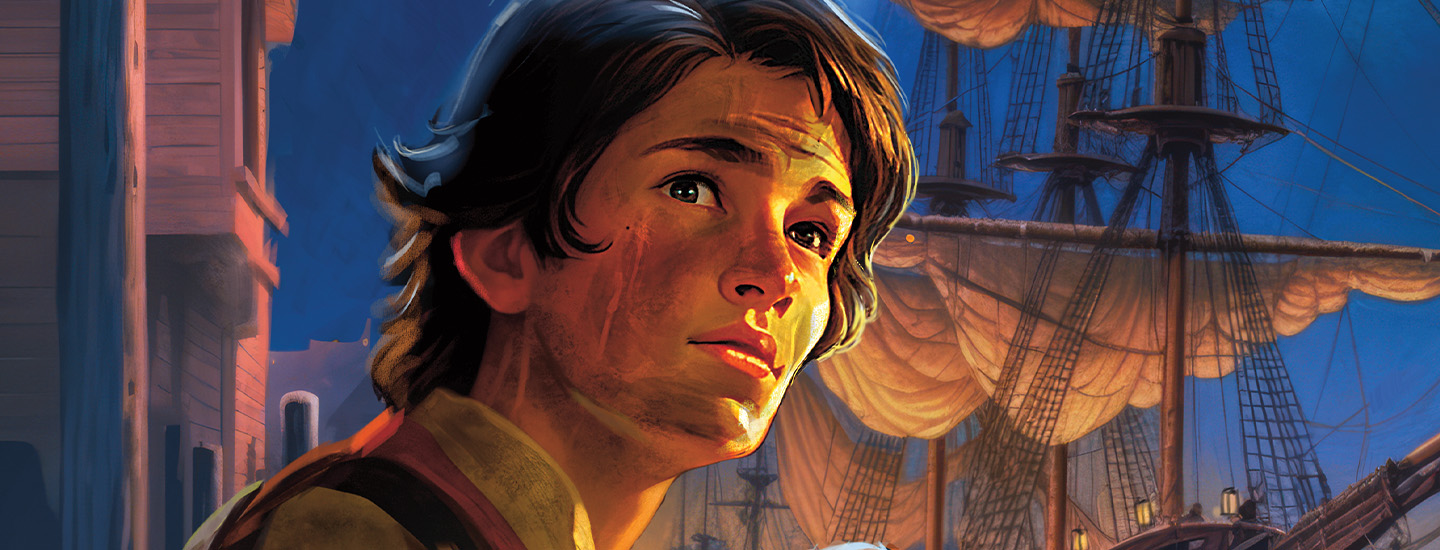

As for Joshua? He joined the revolution himself, fighting in several battles. In 1826, nearing 70 years old, he became one of the first people to tell a reporter a long-held secret—the role he and others had played decades earlier in an incident that was just beginning to become an American legend: the Boston Tea Party.