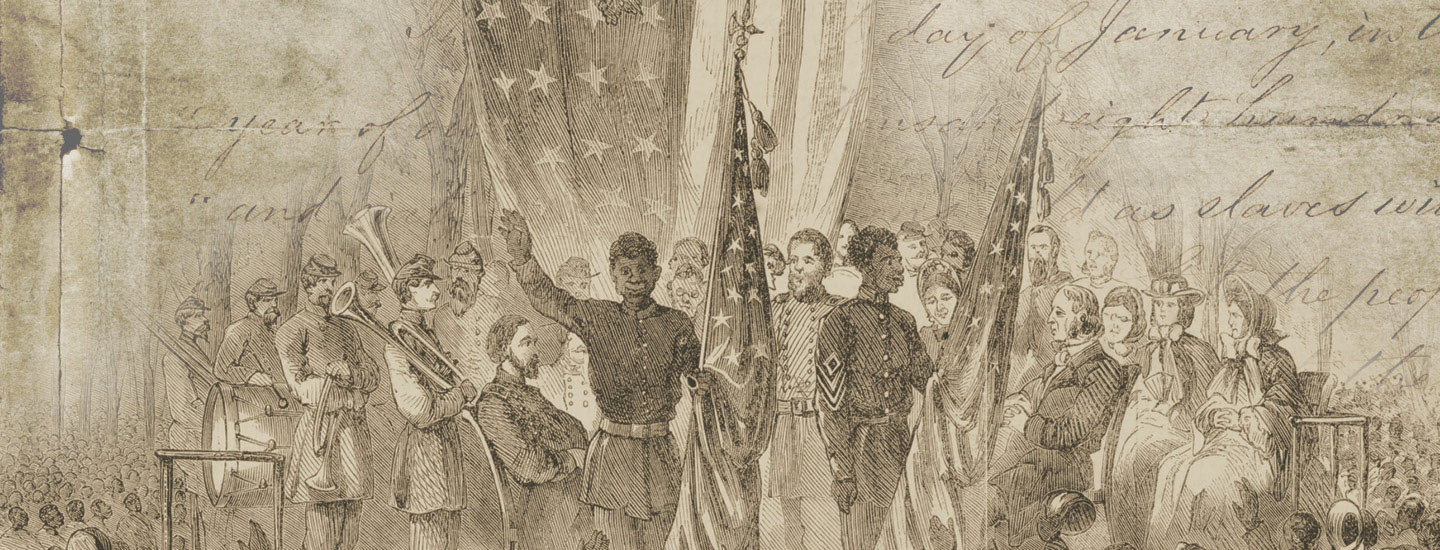

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Famous orator Frederick Douglass called for an end to slavery.

For two long days, it was as if much of the United States was holding its breath—either in anticipation or in anger. Since April 1861, the country had been divided by the brutal Civil War. But on January 1, 1863, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln was expected to issue a decree that would change the lives of millions.

Beginning on New Year’s Eve, formerly enslaved people and their supporters throughout the nation paused for something like hope. Many waited in churches and assembly halls. Thousands of Black Americans met together in camps where most of them had lived since escaping from slavery.

The great orator Frederick Douglass, who had fled enslavement himself years before, gathered with 3,000 people at the Tremont Temple in Boston, Massachusetts. “We were waiting and listening as for a bolt from the sky,” he would later write.

Deep into the evening of January 1, that bolt finally came. Word arrived that the president had signed the Emancipation Proclamation. With the stroke of a pen, Lincoln had declared the enslaved people of the Southern states “forever free.” The historic document would change the course of the war—and of the entire nation.

For two long days, it was as if much of the United States was holding its breath. People waited in anticipation or in anger. Since April 1861, the country had been divided by the brutal Civil War. But on January 1, 1863, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln was expected to issue a decree that would change the lives of millions of people.

Beginning on New Year’s Eve, formerly enslaved people and their supporters throughout the nation paused for something like hope. Many waited in churches and assembly halls. Thousands of Black Americans met in camps where most of them had lived since escaping from slavery.

The great orator Frederick Douglass had fled enslavement himself years before. He gathered with 3,000 people at the Tremont Temple in Boston, Massachusetts. “We were waiting and listening as for a bolt from the sky,” he would later write.

Deep into the evening of January 1, that bolt finally came. Word arrived that the president had signed the Emancipation Proclamation. With the stroke of a pen, Lincoln had declared the enslaved people of the Southern states “forever free.” The historic document would change the course of the war. It would change the entire nation too.