Stephanie Remer/Cherokee Nation

Whitney Roach

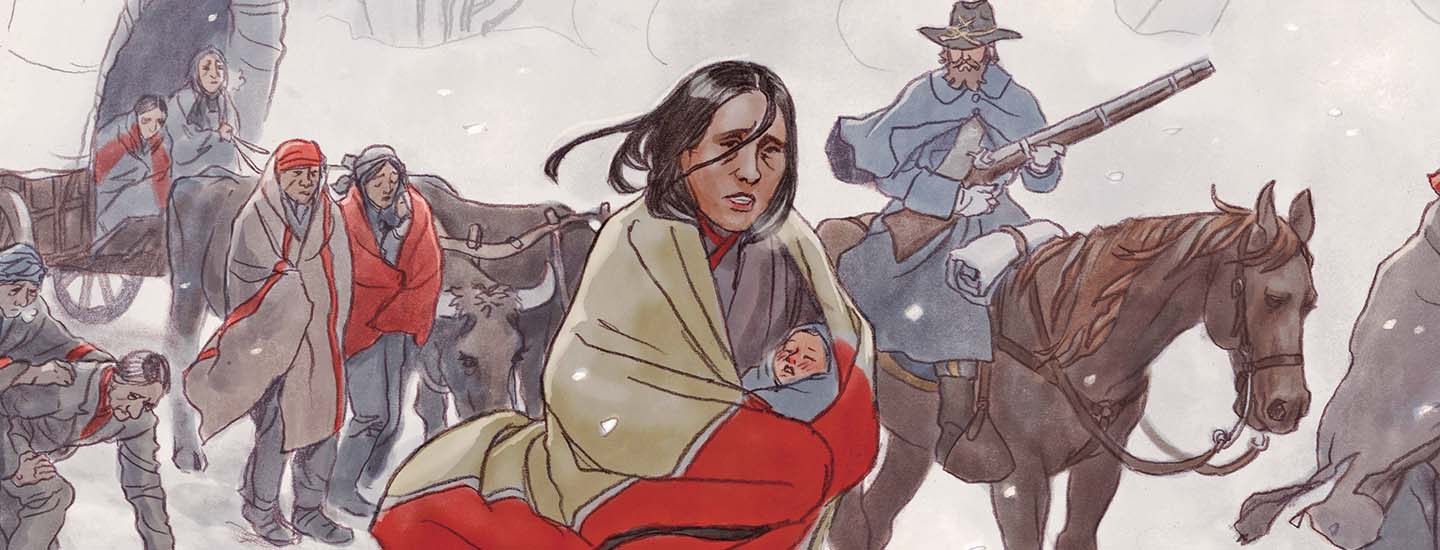

They trudged over rough terrain, battling snow, sleet, and chilling winds. Many traveled by foot—often without shoes. At night, they slept on the frozen ground. They had hardly anything to eat.

The marchers were part of the roughly 16,000 Cherokee people driven from their homeland by the U.S. government. Starting in the summer of 1838 and stretching into the winter of early 1839, Cherokee citizens were ordered to walk hundreds of miles to unfamiliar territory. Their tragic journey is known as the Trail of Tears.

“They were forced out of their houses and off their land,” explains Whitney Roach, age 23. She is a citizen of the Cherokee Nation. “They had to leave a lot of their belongings and take what they could on their backs.”

To honor her ancestors, Roach took part in the annual Remember the Removal Bike Ride this past June. During the 19-day trip, she and eight other cyclists retraced the Trail of Tears (see map, below).

“Seeing where our people had been and what they went through is a heavy thing to hold in your heart,” explains Roach. “I’ve never felt closer to my ancestors.”

They trudged over rough terrain, battling snow, sleet, and cold winds. Many traveled by foot—often without shoes. At night, they slept on the frozen ground. They had hardly anything to eat.

The marchers were part of the roughly 16,000 Cherokee people driven from their homeland by the U.S. government. Cherokee citizens were ordered to walk hundreds of miles to unknown territory. It started in the summer of 1838 and stretched into the winter of early 1839. That tragic journey is known as the Trail of Tears.

“They were forced out of their houses and off their land,” explains Whitney Roach, age 23. She is a citizen of the Cherokee Nation. “They had to leave a lot of their belongings and take what they could on their backs.”

To honor her ancestors, Roach took part in the annual Remember the Removal Bike Ride this past June. She and eight other cyclists retraced the Trail of Tears (see map, below). It was a 19-day trip.

“Seeing where our people had been and what they went through is a heavy thing to hold in your heart,” explains Roach. “I’ve never felt closer to my ancestors.”