Jim McMahon/Mapman®

Think about your favorite book. How much time would it take you to copy it entirely by hand? In the early 1400s, most books were still made that way. Sounds exhausting, right?

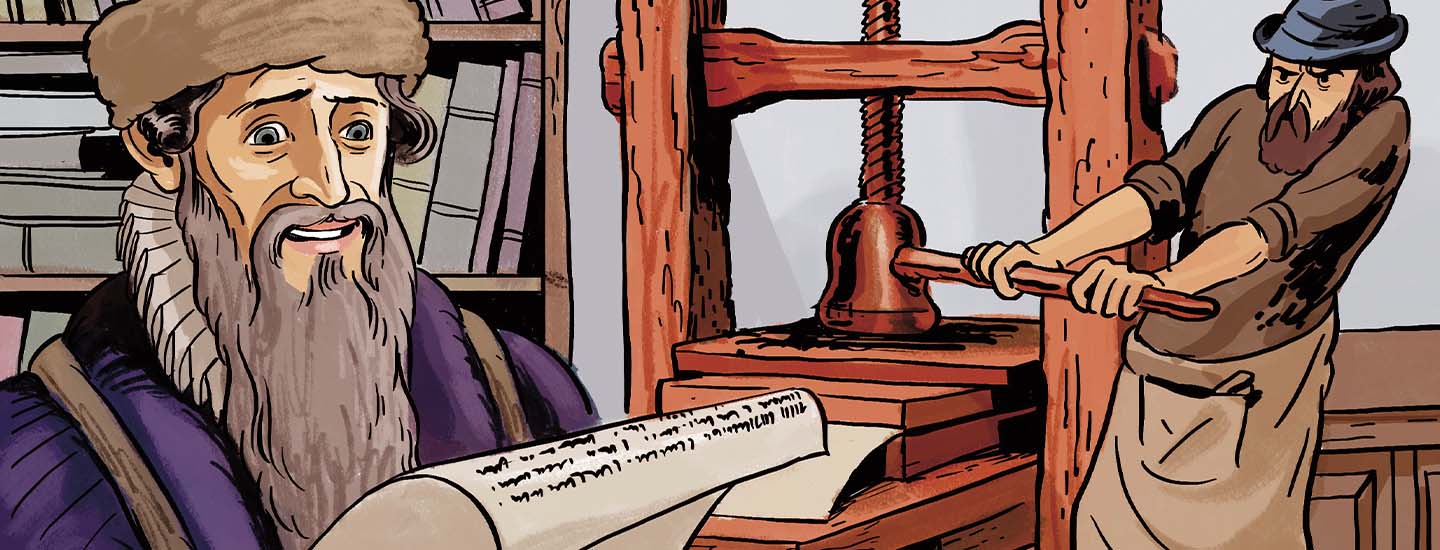

German inventor Johannes Gutenberg had a better idea. He developed a printing press with individual metal letters that could be rearranged and reused many times to print an entire page of text at once.

Here’s how it worked: The metal letters were set in place to spell out a section of text, then coated with ink. That block of text was then hand cranked onto a sheet of paper, making a copy. The printing press could create about 250 pages an hour. That made it possible to mass-produce printed materials for the first time.

In 1455, Gutenberg had a hit with his first major effort—a printing of the Bible. Now known as the Gutenberg Bible, it’s widely considered the first modern book. Gutenberg printed about 180 copies. (If you happen to find an original copy, hang on to it—it’s worth more than $35 million today!)

Gutenberg’s invention made books cheaper and more accessible for ordinary people. It also allowed scholars to share their knowledge with a wide audience. That helped spread the wealth of ideas in art, culture, and science that sprang up in Europe between the 14th and 17th centuries—a period known as the Renaissance—which led to even more key innovations.

Think about your favorite book. How much time would it take to copy it by hand? In the early 1400s, most books were still made that way. Sounds exhausting, right?

German inventor Johannes Gutenberg had a better idea. He developed a printing press with individual metal letters. They could be rearranged and reused many times to print an entire page of text at once.

Here is how it worked. The metal letters were set in place to spell out a section of text. They were coated with ink. That block of text was then hand cranked onto a sheet of paper. That made a copy. The printing press could create about 250 pages an hour. That made it possible to mass-produce printed materials for the first time.

In 1455, Gutenberg had a hit with his first major effort. It was a printing of the Bible, now known as the Gutenberg Bible. It is widely considered the first modern book. Gutenberg printed about 180 copies. (If you happen to find an original copy, hang on to it. It is worth more than $35 million today!)

Gutenberg’s invention made books cheaper and more accessible for ordinary people. It also let scholars share their knowledge with a wide audience. That helped spread the wealth of ideas in art, culture, and science that sprang up in Europe between the 14th and 17th centuries. That period is known as the Renaissance. It led to even more key innovations.