Eight teens were recently invited to a restaurant in the United Kingdom (U.K.) as part of a filmed experiment. Each teen was handed a sealed envelope and a menu with more than 50 items. Then they were asked to order one item off the menu.

The teens all picked the same thing: the restaurant’s “triple dipped chicken.” After receiving their meals, the teens opened their envelopes and each pulled out a piece of paper. They were in shock: The words triple dipped chicken were written on it. The producers of the film had correctly predicted what each teen would order.

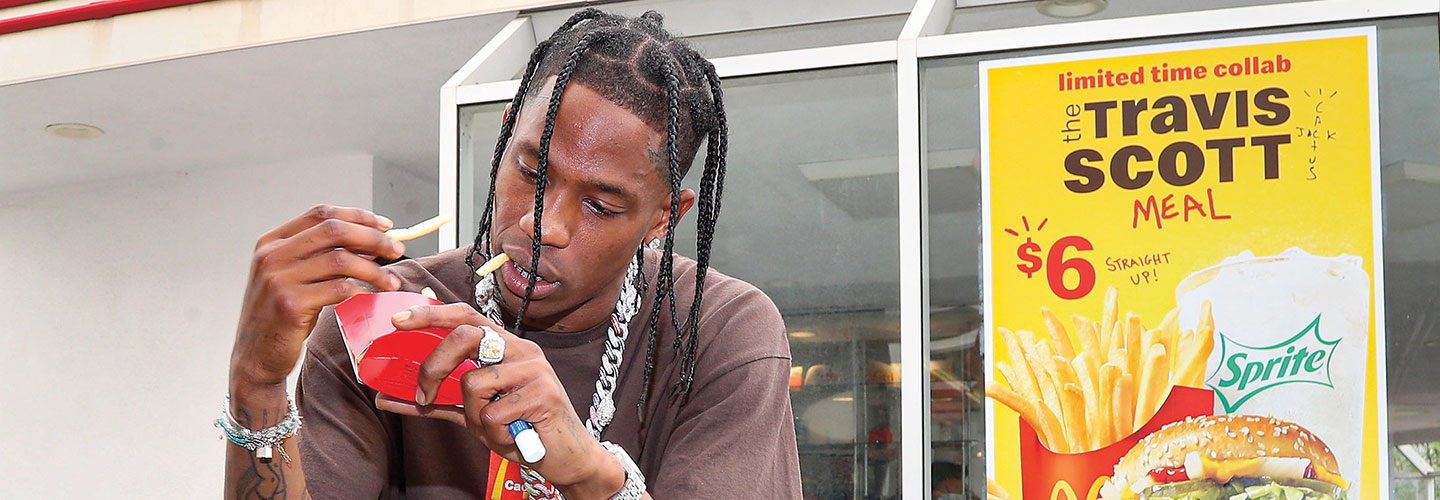

How? By using the same techniques junk food companies employ to market their products. Leading up to the teens’ visit, the producers had bombarded them with ads for the fried chicken dish—on Instagram, in cabs, and on posters along the way to the restaurant (see photos, below). Even though the teens said that they hadn’t noticed the ads, it was clear the marketing had influenced their decisions.

Eight teens were recently invited to a restaurant in the United Kingdom (U.K.). They were part of a filmed experiment. Each teen was handed a sealed envelope. Each was also given a menu with more than 50 items. Then each teen was asked to order one thing from that menu.

The teens all picked same thing: the “triple dipped chicken.” After getting their meals, they opened their envelopes. Each pulled out a piece of paper. They were shocked. It had the words triple dipped chicken on it. The film’s producers had correctly predicted what each teen would order.

How? By using the same techniques junk food companies use to market their products. Before the teens arrived, the producers had bombarded them with ads for the fried chicken dish. The ads were on Instagram and in cabs. Ads were also on posters on the way to the restaurant (see photos, below). The teens said that they had not noticed the ads. But it was clear the marketing had influenced their decisions.