Until the moment disaster struck, January 15, 1919, was a perfectly lovely day.

The weather was unusually warm for winter in Boston, Massachusetts. Around noon, a neighborhood called the North End was bustling with life. Workers ate their lunches in the mild air. Large ships pulled in and out of nearby Boston Harbor. The elevated train rumbled overhead on its tracks.

Antonio Distasio, 9, was out in the street with his sister Maria and his friend Pasquale Iantosca, both 10. Members of the North End’s large Italian immigrant community, they were helping their families by gathering scrap firewood.

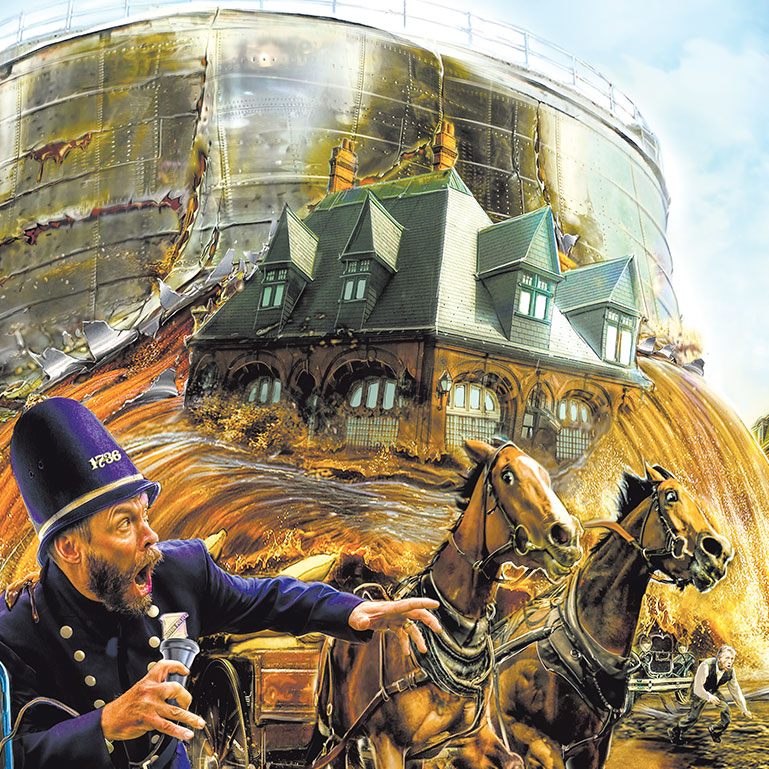

By chance, the kids happened to be next to the neighborhood’s major eyesore: a 50-foot-tall steel tank filled with molasses—a thick syrup that was once a popular sweetener. People hated the ugly tank, which cast a shadow over the neighborhood. It often oozed brown goo. And when it was full, as it was now, the tank would groan as if it were a great beast suffering from a stomachache.

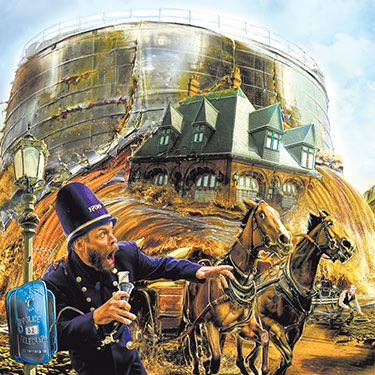

At about 12:40 p.m., patrolman Frank McManus was making a call at a phone box on Commercial Street, near the tank. Suddenly, he heard “a tremendous rumbling, grinding sound,” he later said, along with “the rat-tat-tat of what sounded like machine-gun bullets.” That was actually the sound of thousands of metal rivets—which held the tank together—popping out.

McManus turned to see the giant structure burst apart and a wall of thick, dark liquid come roaring out.

“Send all available rescue vehicles and personnel immediately!” he managed to shout into the phone. “There’s a wave of molasses coming down Commercial Street!”

January 15, 1919, was a perfectly lovely day—until the moment disaster struck.

The weather was quite warm for winter in Boston, Massachusetts. Around noon, a neighborhood called the North End was lively and busy. Workers ate their lunches in the mild air. Large ships pulled in and out of nearby Boston Harbor. The elevated train ran on its tracks.

Antonio Distasio, 9, was out in the street. So were his sister Maria and his friend Pasquale Iantosca, both 10. They were members of the North End’s large Italian immigrant community. The children were helping their families by gathering scrap firewood.

By chance, the kids happened to be next to the neighborhood’s major eyesore, a 50-foot-tall steel tank. It was filled with molasses. That thick syrup was once a popular sweetener. People hated the ugly tank. It cast a shadow over the neighborhood. It often oozed brown goo. And when it was full, as it was now, the tank would groan. It sounded like a huge beast with a stomachache.

At about 12:40 p.m., patrolman Frank McManus was making a call at a phone box on Commercial Street. That was near the tank. Suddenly, he heard “a tremendous rumbling, grinding sound,” he later said. He also heard “the rat-tat-tat of what sounded like machine-gun bullets.” That was actually the sound of thousands of metal rivets popping out. The rivets had held the tank together.

McManus turned to see the giant structure burst apart. A wall of thick, dark liquid came roaring out.

“Send all available rescue vehicles and personnel immediately!” he managed to shout into the phone. “There’s a wave of molasses coming down Commercial Street!”