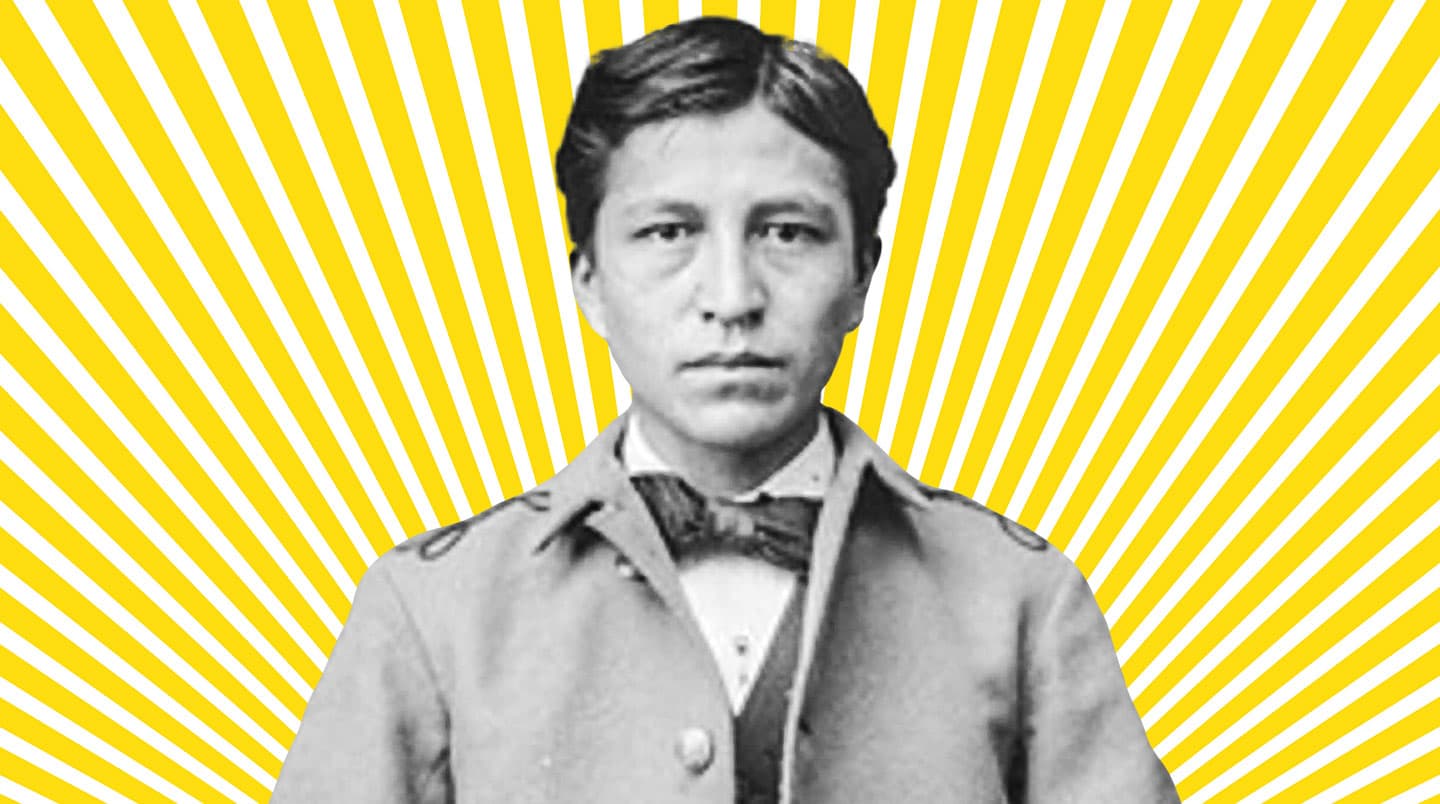

Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, PA.

Luther Standing Bear as a young boy, when he was known as Ota Kte

“Choose your new name,” said the teacher.

The 11-year-old boy looked at the marks on the blackboard. Having grown up speaking the language of his Lakota Sioux (soo) people, he couldn’t understand them. He’d been told that each line of markings was a different white man’s name. Now he had to pick one.

But the boy already had a name: Ota Kte (OH-tuh kuh-TAY). His father, the Lakota chief Standing Bear, had given it to him when he was born in 1868. Standing Bear had taught him how to ride a horse and hunt buffalo using a bow and arrow.

His father had also raised him to follow a code of conduct in which honor, bravery, and service to one’s people were more important than life itself. It was a code followed by the Native American nations of the Great Plains, where Ota Kte’s ancestors had lived for generations.

For instance, his people believed there was no greater honor than to show bravery in battle by approaching an enemy and simply touching him rather than shooting him.

But Ota Kte was no longer with his people on the Pine Ridge reservation in what would later become South Dakota. Instead, he was 1,500 miles away in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. There, he was a member of the first class of students at the United States Indian Industrial School. The school was designed to teach him the ways of the white man—and erase his Native American identity.

“Indicate the name that will be yours,” the white teacher said. She placed a long stick in Ota Kte’s hand.

The boy recognized the challenge he now faced: adapting to the world of the white people whose weapons and diseases had devastated his people. Thanks to his father’s lessons, he knew how to respond.

“I took the pointer and acted as if I was about to touch an enemy,” he would write years later.

The name he chose was Luther. From that day on, Luther Standing Bear would live partly in the white man’s world. But he would always carry his former life in his heart—and never stop fighting for his people.

“Choose your new name,” said the teacher.

The 11-year-old boy looked at the marks on the blackboard. He could not understand them because he had grown up speaking the language of his Lakota Sioux (soo) people. He had been told that each line of markings was a different white man’s name. Now he had to pick one.

But the boy already had a name. It was Ota Kte (OH-tuh kuh-TAY). His father had given it to him when he was born in 1868. His father was Standing Bear, the Lakota chief. Standing Bear had taught him how to ride a horse. He had taught him to hunt buffalo using a bow and arrow.

The boy’s father had also raised him to follow a code of conduct in which honor, bravery, and service to one’s people were more important than life itself. It was a code followed by the Native American nations of the Great Plains. That is where Ota Kte’s ancestors had lived for generations.

For instance, his people believed there was no greater honor than to show bravery in battle. They believed bravery was approaching an enemy and simply touching him rather than shooting him.

But Ota Kte was no longer with his people on the Pine Ridge reservation in what would later become South Dakota. Instead, he was 1,500 miles away in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. There, he was a member of the first class of students at the United States Indian Industrial School. The school was designed to teach him the ways of the white man. It was meant to erase his Native American identity.

“Indicate the name that will be yours,” the white teacher said. She placed a long stick in Ota Kte’s hand.

The boy recognized the challenge he now faced. He was supposed to adapt to the world of the white people whose weapons and diseases had devastated his people. Thanks to his father’s lessons, he knew how to respond.

“I took the pointer and acted as if I was about to touch an enemy,” he would write years later.

The name he chose was Luther. From that day on, Luther Standing Bear would live partly in the white man’s world. But he would always carry his former life in his heart. And he would never stop fighting for his people.