Jim McMahon/Mapman®

In the middle of the Pacific Ocean lies a tiny, remote island whose most famous residents stand guard along the edges of the rocky terrain. Most of them face inward so they can watch over the island’s other inhabitants, but a few look out to sea to guide travelers to land. They are hundreds of years old and weigh an average of 14 tons each.

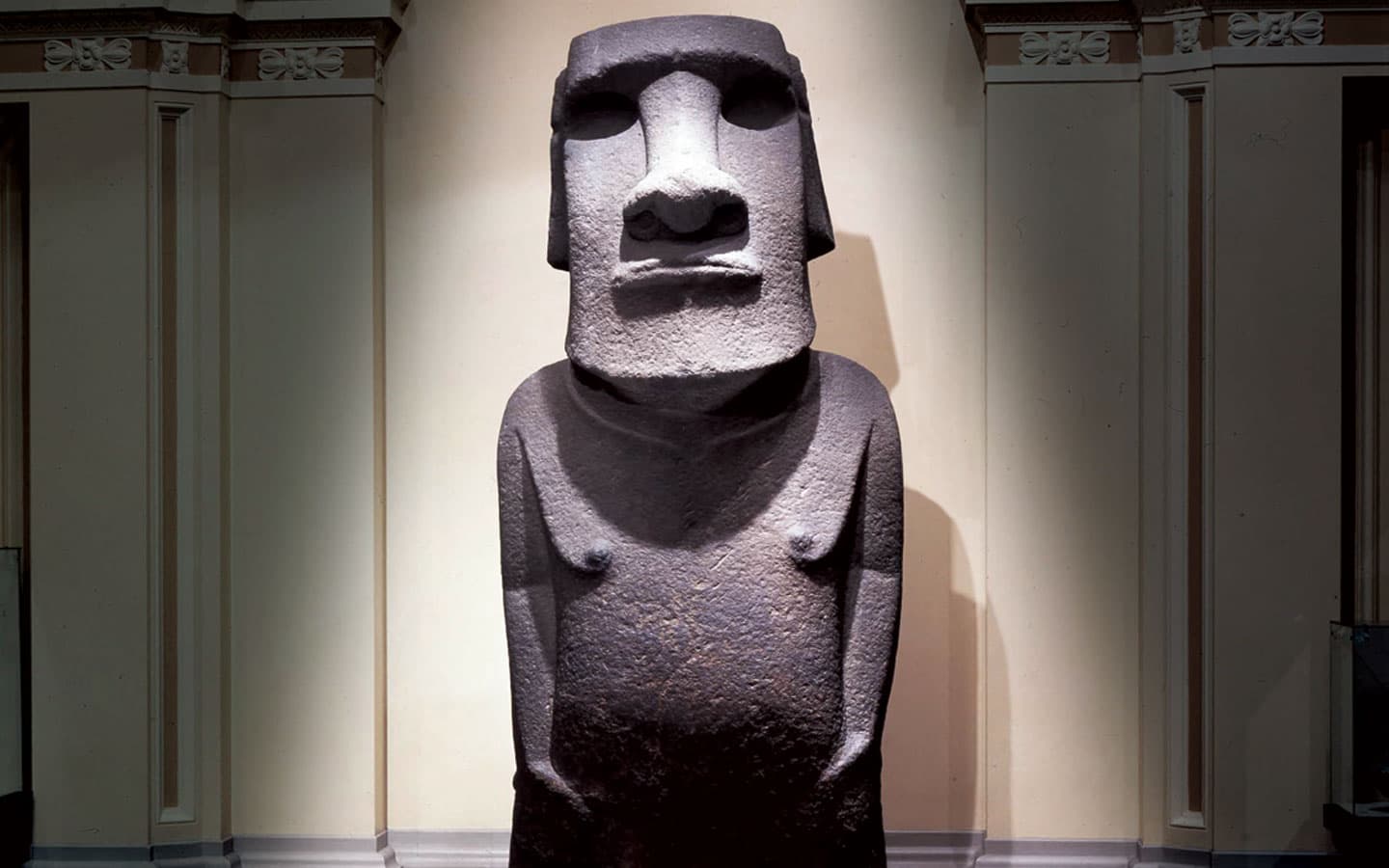

These legendary islanders are actually massive stone statues called moai (MOH-eye). There are more than 800 of them on Easter Island, also known as Rapa Nui (RAH-puh NOO-ee) after the indigenous people who settled there centuries ago. The 14-mile-long volcanic island is part of the South American country of Chile, located 2,200 miles away.

The statues were carved by the Rapa Nui people and are between 400 and 900 years old. The sculptures—known for their oversized heads—represent Rapa Nui ancestors, and they are considered sacred by descendants of the ancient civilization who still live on the island today.

However, a few of the moai are missing from their native home. One statue has been on display at the British Museum in London, England, for about 150 years and is one of the institution’s most popular exhibits.

But that may not be the case for much longer. Rapa Nui leaders recently announced that they want the statue back. Their request is not unique. Many museums around the world are facing similar pressure to return artwork and other historical objects to their homelands.

The issue has reignited a debate among art experts and government officials: Do ancient artifacts belong in the places they came from or should they be displayed in popular museums where millions of people can appreciate them?

In the middle of the Pacific Ocean lies a tiny, remote island. Its most famous residents stand guard along the edges of the rocky terrain. Most of them face inward so they can watch over the island’s other inhabitants. A few look out to sea to guide travelers to land. They are hundreds of years old. And they weigh an average of 14 tons each.

These legendary islanders are actually huge stone statues called moai (MOH-eye). There are more than 800 of them on Easter Island. The island is also known as Rapa Nui (RAH-puh NOO-ee) after the indigenous people who settled there centuries ago. The volcanic island is 14 miles long. It is part of the South American country of Chile, located 2,200 miles away.

The statues were carved by the Rapa Nui people and are between 400 and 900 years old. These sculptures, known for their oversized heads, represent Rapa Nui ancestors. They are considered sacred by descendants of the ancient civilization who still live on the island today.

However, a few of the moai are missing from their native home. One statue has been on display at the British Museum in London, England, for about 150 years. It is one of the institution’s most popular exhibits.

But that may not be so for much longer. Rapa Nui leaders recently announced that they want the statue back. Their request is not unique. Many museums around the world are facing similar pressure to return artwork and other historical objects to their homelands.

The issue has renewed a debate among art experts and government officials. Do ancient artifacts belong in the places they came from? Or should they be displayed in popular museums where millions of people can appreciate them?