Narrator D: On December 7, a small fleet of fishing boats in Southern California is headed out to sea. Jeanne’s father, Ko, is on one of the boats. His sons Bill and Woody are his crew. From the shore, women and children are waving goodbye.

Jeanne Wakatsuki: When will they be back?

Riku: Two days? A week? It depends on how good the fishing is and how much they can catch.

Jeanne: Wait, look! The fleet is coming back already.

Chizu: Maybe someone is hurt!

Jeanne: But why would all the boats come back?

Riku: Something must be wrong.

Narrator E: A man runs out of the nearby fish cannery.

Man (shouting): We just heard it on the radio! The Japanese have bombed Pearl Harbor in Hawaii!

Narrator A: That night, the Wakatsuki family—and people all across the U.S.—listen to the radio for news.

Newscaster: Today at 7:55 a.m. Hawaii time, some 200 Japanese aircraft bombed the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor. More than 2,000 servicemen were killed. Another thousand or so were wounded.

Narrator B: Ko, who was born in Japan, burns the Japanese flag.

Jeanne: Why is Papa doing that?

Riku: So people don’t think we sympathize with the Japanese attackers.

Jeanne: Why would they think that? We’re Americans.

Riku: Yes. But they don’t know what’s in our hearts. They don’t know we are loyal to America.

Narrator C: Two weeks after the Pearl Harbor attack, FBI agents come to the house and take Ko away. The family is in turmoil.

Woody: The newspaper says that Papa used his boat to sneak secrets and supplies to Japanese subs.

Kiyo: Papa loves this country!

Lillian: And we’re all proud to be American! How can they doubt us?

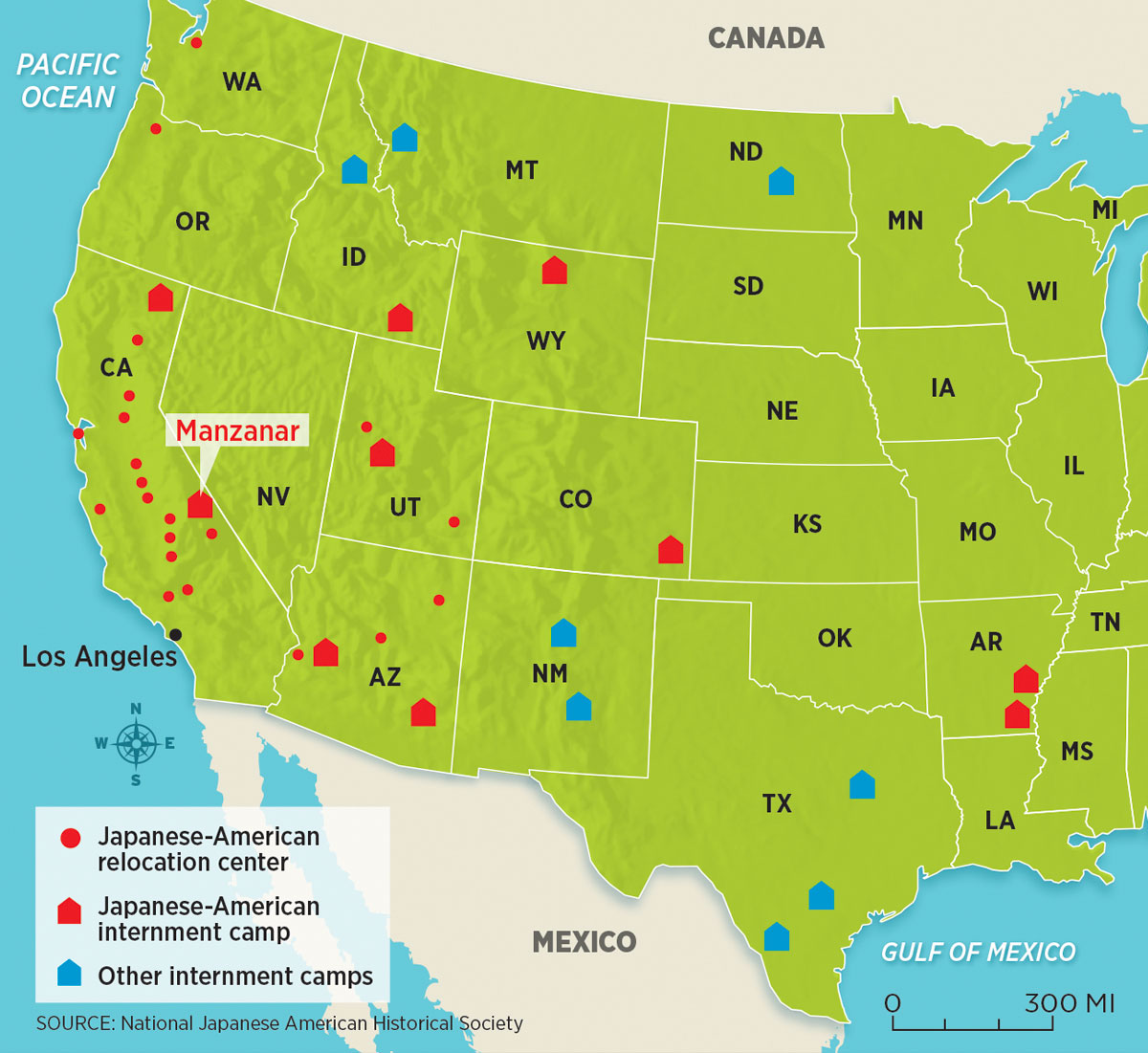

Narrator D: The U.S. government labels Ko a hostile “enemy alien.” He’s sent to a prison in North Dakota. It is weeks before his family learns what happened to him.