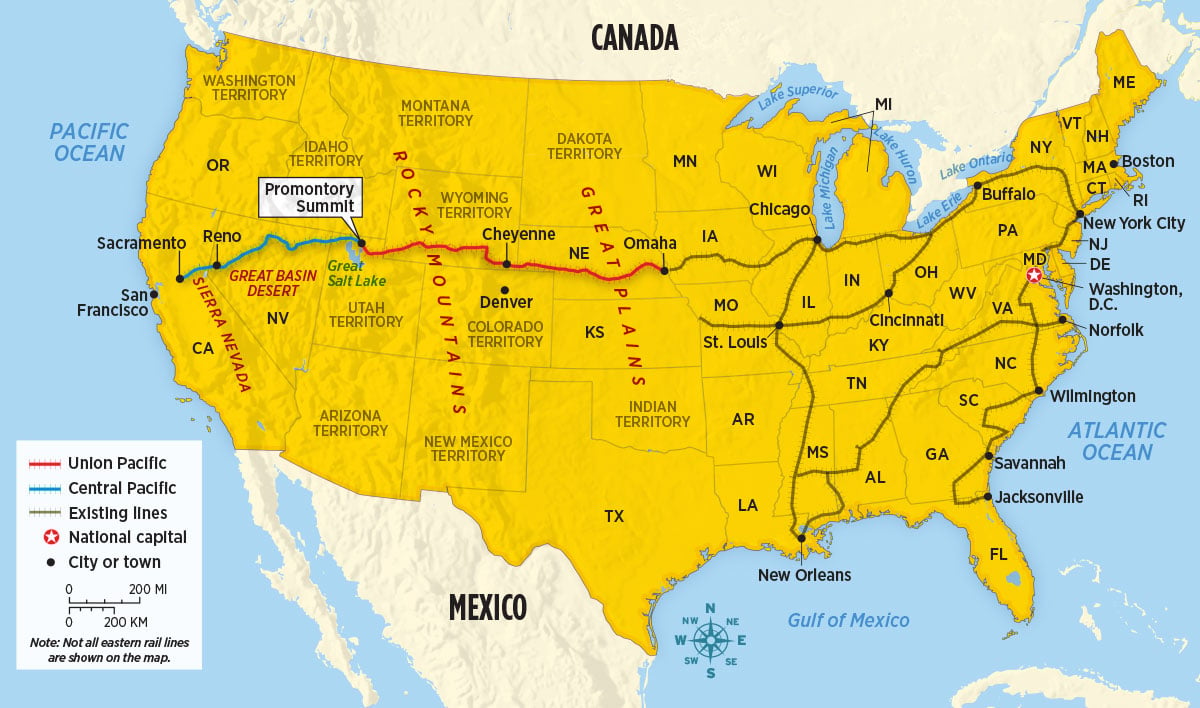

It’s May 10, 1869, and a spirited crowd has gathered in isolated Promontory Summit, deep in Utah Territory, to make history. Little more than a collection of tents and makeshift workers’ shacks, it’s an unlikely spot from which to witness the transformation of the United States. Yet thousands of people have gathered here to do just that.

All eyes are on Leland Stanford, president of the Central Pacific Railroad, as he raises a hammer to tap a golden spike into the track. Clang! Cheers erupt all around and railroad engineers blow their whistles. Men give speeches and pop open bottles of champagne.

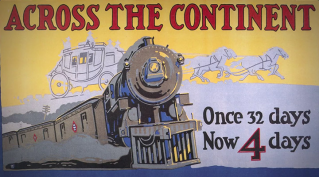

Then a telegraph operator types out a single word: “DONE.” In an instant, people in New York, Chicago, and other cities receive the news and celebrate. Cannons blast, bells ring out. After years of planning and work, America’s first transcontinental railroad is complete. From coast to coast, the entire country is now connected by rail.