Within months of the war’s outbreak, Hitler had invaded much of Europe. Many people in the growing German empire soon turned against their Jewish neighbors, setting synagogues on fire, destroying Jewish businesses, and beating Jews in the streets. The vicious attacks prompted hundreds of thousands of Jews to try to flee their homes.

But many of them had nowhere to go. Several nations, including the U.S., had set quotas that limited the number of refugees they would allow in. Sonia’s family was trapped.

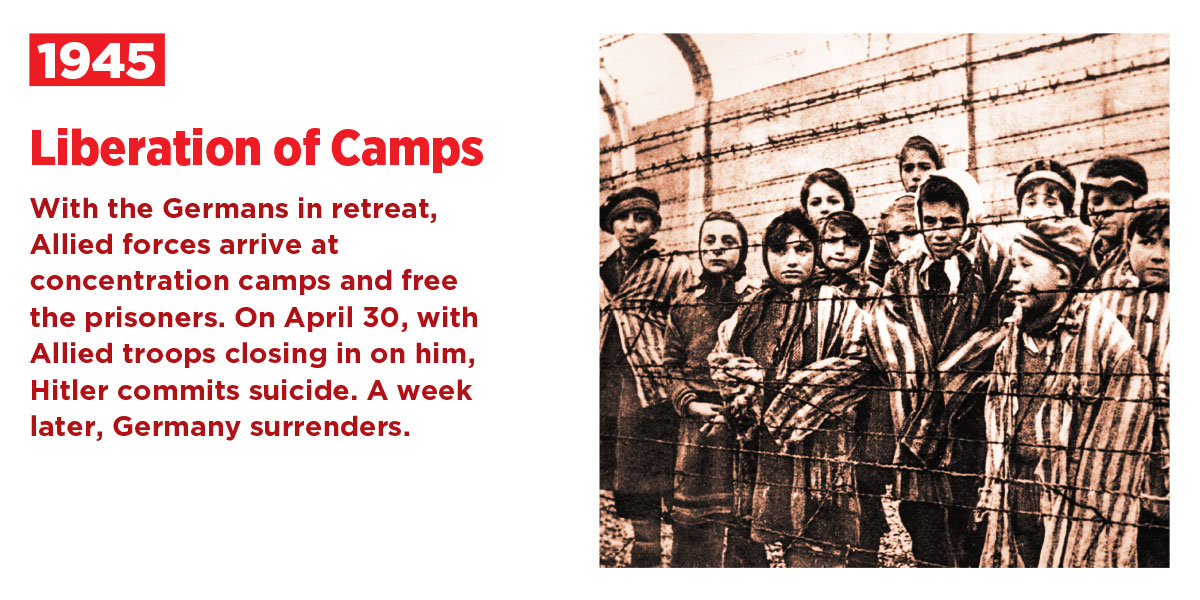

When the Nazis arrived in Luboml, they forced the town’s 8,000 Jews into a crowded ghetto surrounded by fencing and barbed wire. Sonia, her parents, and 13 friends and relatives were crammed into a two-room house. By then, her brothers had already left to fight the Nazis—one with a partisan unit, the other with the Soviet army. She would never see them again.

Each resident of the ghetto was given just one slice of bread a day and made to perform backbreaking work for hours at a time. Instead of going to school, Sonia and other young girls had to lug huge steel rails. If they stopped to catch their breath for even a second, they risked being beaten by Nazi guards.

Then, in the fall of 1942, rumors spread that the Nazis were planning to kill all the Jews in the ghetto. For two days, Sonia and the 15 other people in the house hid inside—and didn’t dare make a sound. Every few minutes, they could hear German trucks passing by outside. But it wasn’t until years later that Sonia found out what happened: The Nazis had rounded up all the Jews they could find—1,700 men, women, and children—and dragged them to the countryside. There, they were lined up in front of giant pits and shot.