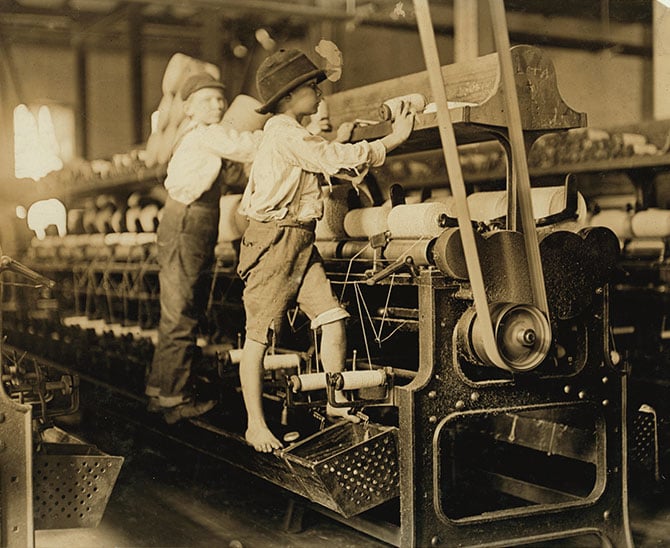

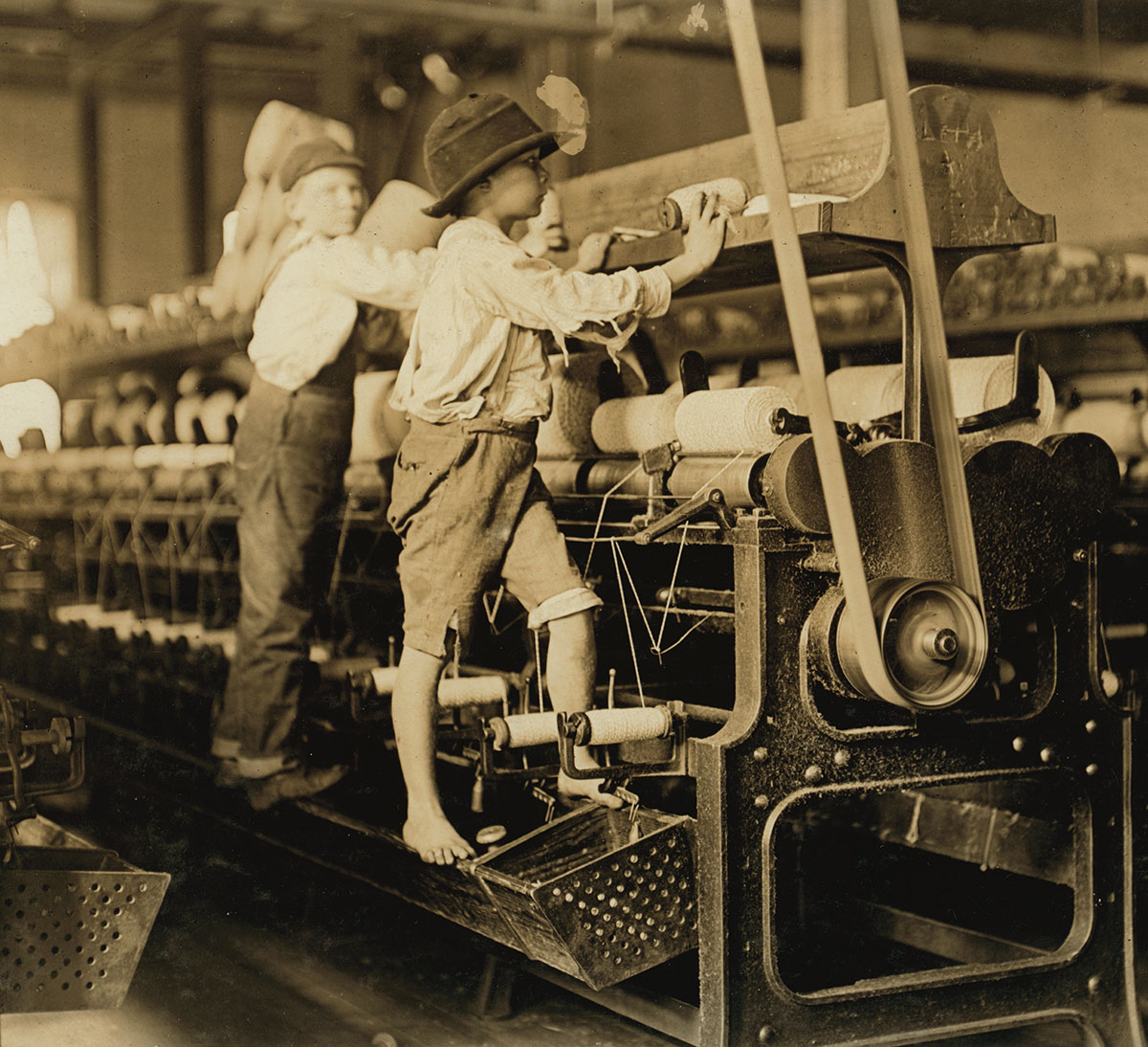

In a split second, Camella Teoli’s life changed forever. It was late in the afternoon. The 12-year-old factory worker had been on her feet for hours changing spools of thread on machines that spun wool into fabric. All day, she’d had to keep her long hair pinned up around the machinery’s whirring belts, gears, and rollers. Finally, tired and uncomfortable, Camella let her hair down. She turned—and suddenly, a spinning roller yanked the end of her brown locks. Before she could even cry out, her hair was sucked into the enormous machine.

That day in July 1909 had already seemed endless. Like many of the other