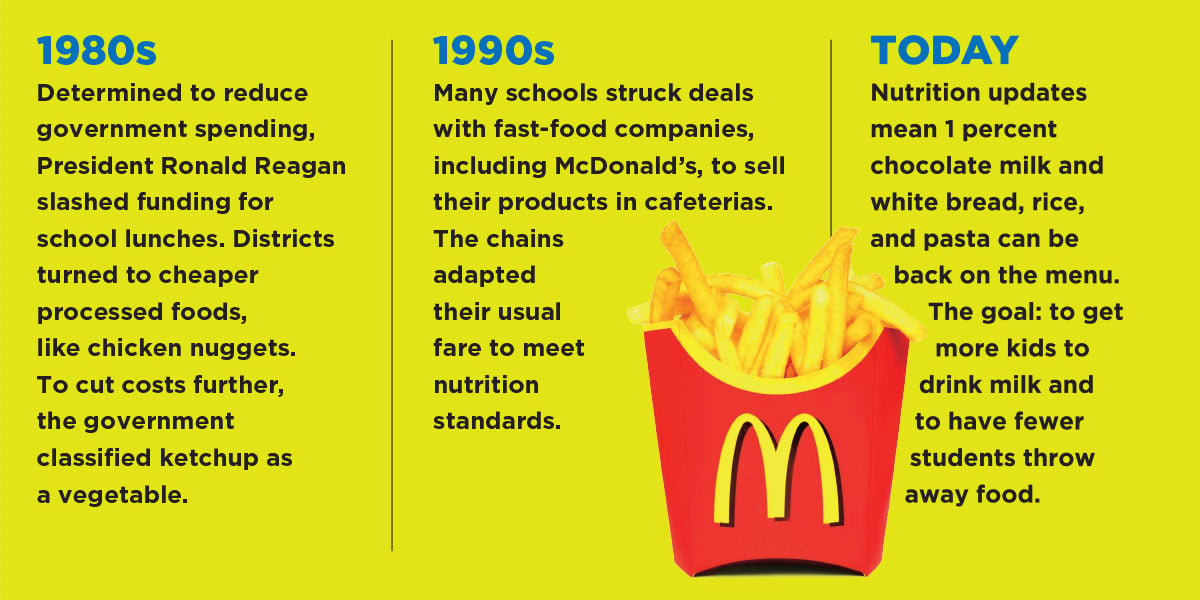

For all the debate, the changes won’t affect many school cafeterias, predicts Gay M. Anderson. She’s the president of the School Nutrition Association, which represents cafeteria workers nationwide.

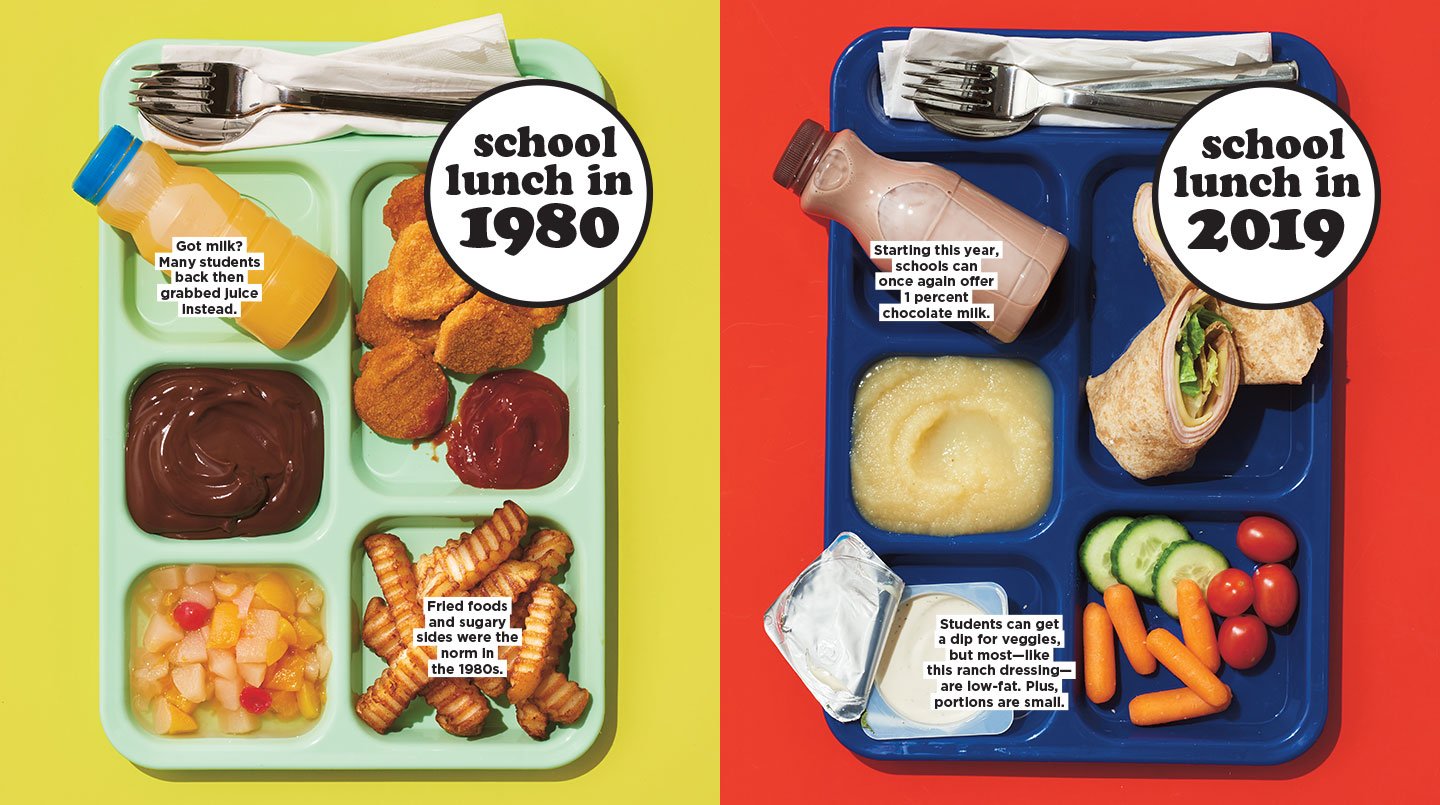

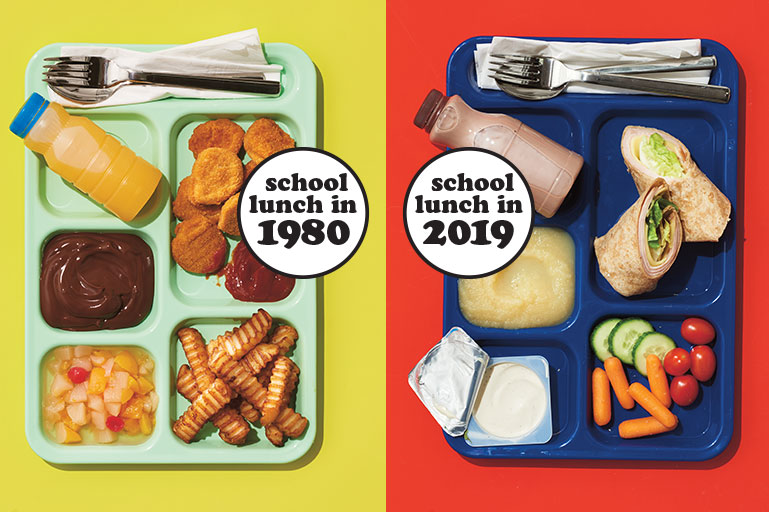

Schools aren’t likely to get rid of healthier options if kids are eating them, Anderson says. Also, even though white bread and 1 percent chocolate milk are now allowed, nutrition directors may have trouble fitting them into the menu while still meeting calorie, fat, and sodium limits, which have stayed the same.

Still, some schools may now serve white pasta, flour tortillas, or white rice instead of the once-required whole-grain versions. That’s not necessarily bad—at least students will eat more of the food, Anderson says. Plus, some experts say, serving flavored 1 percent milk again could help boost milk consumption.

In the end, Anderson says, it’s all about balance. “We’re trying to find a happy, healthy medium for our students,” she explains. “We want the food in their bellies rather than going into the garbage can.”