Monumental Battle

Why a push to remove Confederate monuments has sparked violence, protests, and heated debate

Protesters dressed in camouflage and gripping assault rifles gathered near a park in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August. They had assembled for a rally of white supremacists—people who believe the white race is superior to all others. According to their leaders, they were in Charlottesville to march against the city’s plan to remove a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. He led the armies of the South during the Civil War (1861-65), which pitted the North (called the

But the protesters weren’t alone. A crowd of people who disagreed with them also arrived to demonstrate. The two sides soon clashed—first with angry chants, then with bottles, pepper spray, and fists. As the violence erupted, an alleged white supremacist plowed his car into the counter-protesters, killing one and injuring 19 others.

Despite the uproar, the city still plans to take down the Lee statue—though opponents have filed a lawsuit to stop its removal. Charlottesville is hoping to follow the lead of several other cities, such as New Orleans, Louisiana, that recently took down Confederate monuments. This past spring, after years of lawsuits and protests, New Orleans removed four such statues, including one of Lee.

The disputes in Charlottesville and New Orleans are just two examples of how the fight over the legacy of the Civil War is still playing out more than 150 years later.

Clashing Views

To many people, Confederate symbols represent slavery—the main cause of the Civil War—and the oppression of blacks in the South for more than a century after that war.

“These statues are not just stone and metal,” says New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu. The monuments celebrate an overly simplified view of the Confederacy, he says, while “ignoring the death, ignoring the enslavement, ignoring the terror that it actually stood for.”

Some people who oppose the removal of Confederate symbols, including the white supremacists who marched in Charlottesville, are members of hate groups that believe the white race should have power over all other races (see sidebar, below). To them, the Confederacy represents a time when whites were firmly in control.

However, other people support keeping the monuments for different reasons. Pierre McGraw is a descendant of Confederate soldiers. He says the statues honor the bravery of Southerners who fought in the Civil War.

To some people, confederate symbols represent racism;

To others, a proud past.

By taking the statues down, he says, “you’re basically ripping out chapters of a history book.”

President Donald Trump joined the debate after the events in Charlottesville, defending Civil War monuments as part of America’s “history and culture.” He also blamed “both sides”—white supremacists and the protesters who opposed them—for the violence. His remarks were widely condemned by both Democrats and Republicans.

North vs. South

In some ways, says Alvin Tillery, a professor of African-American studies at Northwestern University, the battle over Confederate symbols shows how the U.S. “never addressed the legacy of the Civil War or slavery.” Even today, Americans have very different views of why the Civil War was fought.

When the war began, the Southern economy was mostly agricultural, relying on a few million slaves to harvest cotton. Most historians say the war started because of the South’s desire to continue slavery.

However, not everyone agrees with that interpretation. Some say the South fought primarily for states’ rights to decide their own affairs. After the North won the war, Southerners and groups commissioned monuments to help promote that view of the conflict.

Many of the memorials honor Confederate leaders and soldiers without any mention of slavery. For example, a Confederate monument recently removed in St. Louis, Missouri, read: “They battled to preserve the independence of the states.”

Painful History

Honoring Confederate bravery wasn’t the monuments’ only purpose, says James Grossman of the American Historical Association. They also served to rally white Southerners who resented the gains that black Americans achieved after the war, such as the right to vote.

In the 1870s, Southern states began passing Jim Crow laws, which restricted the rights of blacks and segregated them from whites. Over the next few decades, hundreds of Confederate monuments were erected as violence against African-Americans escalated.

The building of Confederate statues surged again during the civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s, Grossman says. Although blacks were making strides toward equality then, there was still resistance to change in the South.

Today, many African-Americans are pained by the monuments’ presence. “I am offended every time I pass [the Lee statue],” Zyahna Bryant, an 11th-grader in Charlottesville, wrote to city officials. “I am reminded over and over again of the pain of my ancestors.”

States Take Action

The movement to rid public property of Confederate symbols has been growing since June 2015, when 21-year-old Dylann Roof—a self-proclaimed racist who openly embraced the Confederate flag—murdered nine black churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina.

Almost immediately, Confederate symbols came under fire. South Carolina and Alabama took down the Confederate flags on their capitol grounds. And public officials began to debate removing Civil War monuments in places such as Richmond, Virginia; St. Louis, Missouri; Austin, Texas; and Orlando, Florida.

At least 60 Confederate monuments in the U.S. have been taken down or renamed in the past two years, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center. Some of the statues are moved to museums.

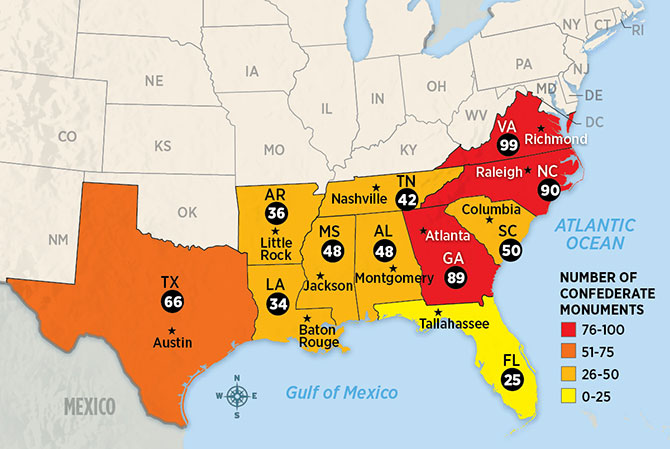

Still, nearly 700 statues remain on display, most in the former Confederacy (see map, below). And many states have no plans to take down their monuments. Some have even passed laws banning the removal of any plaque, statue, or monument on public property that commemorates a historic military figure or event.

The “Whole Story”

In some places, groups are trying to reach a compromise. One approach has been to add more information to Confederate monuments, with background about the people depicted and their legacies.

The U.S. “never addressed the legacy of the civil war or slavery.”

For example, the University of Mississippi kept its controversial Confederate statue but added a plaque. It reads, in part: “Although the monument was created to honor the sacrifice of local Confederate soldiers, it must also remind us that the defeat of the Confederacy actually meant freedom for millions of people.”

Putting the monuments in historical context rather than replacing them is called contextualization. Even this approach isn’t without challenges. It took two years for University of Mississippi officials to agree on the plaque’s wording. And small signs may not be enough to balance every statue, critics say.

Other cities have created new statues honoring African-Americans rather than eliminating Confederate ones. In Richmond, Virginia, a statue of black tennis star Arthur Ashe overlooks the city’s famed Monument Avenue, along with Confederate generals Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson.

“I want Richmond to tell the whole story of its people,” Mayor Levar Stoney recently told Time. “Not just a one-sided story.”

CORE QUESTION: Why are Confederate symbols so controversial?

What Are Hate Groups?

The Ku Klux Klan rallies in July in Charlottesville.

Hate groups promote racism and hatred toward members of different races, religions, and sexual orientations. More than 900 hate groups exist in the United States today, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center. They include the Ku Klux Klan—formed after the Civil War to terrorize newly freed slaves—and

Why are these groups allowed to promote racist views? The answer lies in the Constitution—more specifically, in the First Amendment right to free speech. It protects all Americans’ right to express themselves, even if most people find what they’re saying offensive.

Heritage or Hate?

Most of the Confederate monuments on public display in the U.S. are in the 11 states that were part of the Confederacy during the Civil War (see above). The rest are scattered across 20 other states.

The Civil War, Reimagined

Two upcoming shows portray an alternate history of the Civil War

By Laura Anastasia and Carl Stoffers

What if the Civil War had turned out differently? That’s the question posed by two new alternate-history dramas in the works: HBO’s Confederate and Amazon’s Black America.

In Confederate, the South successfully seceded, slavery still exists south of the Mason-Dixon line, and a third civil war is looming in the present day. Though it hasn’t yet started filming, the TV show—created by the team behind Game of Thrones—has already caused an uproar. Essayist Roxane Gay wrote in The New York Times: “I cannot help worrying that there are people…who will watch Confederate and see it as inspiration, rather than a cautionary tale.”

Days after HBO announced Confederate, Amazon announced Black America, which imagines a world in which freed African-Americans have acquired three states as reparations (or compensation) for slavery. The series is billed as a counter-point to Confederate, despite being in the works for more than a year.

So why the interest in re-examining different outcomes of the Civil War? Says Alvin Tillery, a historian and African-American studies professor at Northwestern University: “The fascination comes directly from the fact that we’ve never really dealt with this history and its legacies in our modern politics and modern life.”