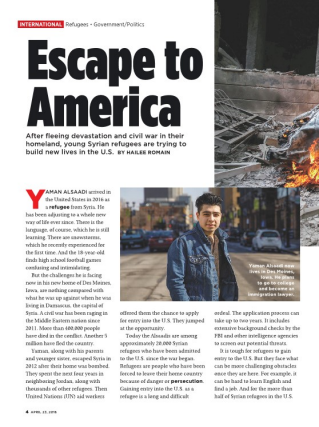

Since Yaman Alsaadi arrived in the United States in 2016 as a

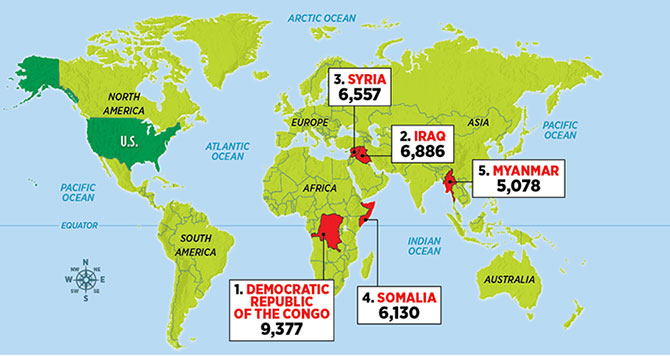

But the challenges he’s facing now in his new home of Des Moines, Iowa, are nothing compared to what he was up against when he was living in Damascus, the capital of Syria. A civil war has been raging in the Middle Eastern nation since 2011. More than 400,000 people have died in the conflict and another 5 million have fled the country.

Yaman, along with his parents and younger sister, escaped Syria in 2012 after their home was bombed. They spent the next four years in neighboring Jordan, along with thousands of other refugees, before United Nations (UN) aid workers offered them the chance to apply for entry into the U.S. They jumped at the opportunity.