One day in the spring of 2016, Kemyriah Patie, a first-grader at Fair Elementary School in Louisville, Mississippi, was accused of saying something inappropriate to another student.

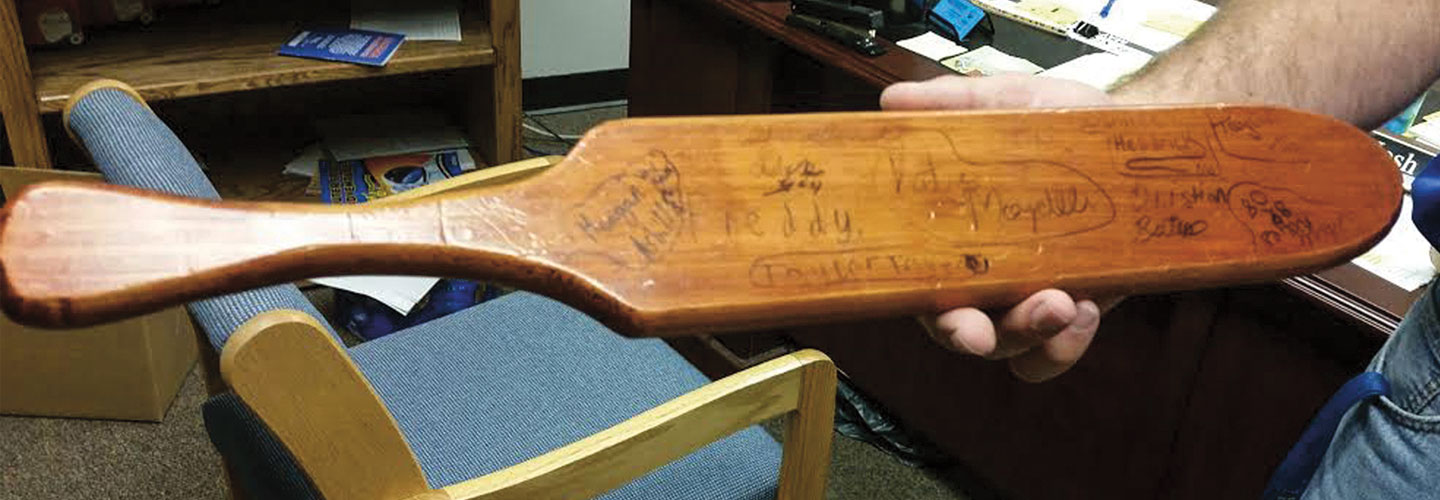

Three teachers administered the punishment. Two held Kemyriah down while a third used a wooden paddle to strike her repeatedly on the backside and legs. Her mother, Shawanda Patie, found out about it after school that day. When she saw bruises all over the backs of her daughter’s legs, she took her to the emergency room.

“I was in an outrage,” Patie says. “My baby couldn’t walk right for a week and a half.”

Physical punishment—also called

While the supporters of corporal punishment say it’s an effective way to discipline students who act out, critics have sought to end the practice. They say it’s cruel and sends kids the wrong message about the use of violence.