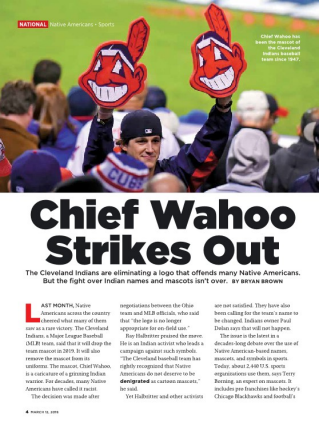

Last month, Native Americans across the country cheered what many of them saw as a rare victory. The Cleveland Indians, a Major League Baseball (MLB) team, announced that it will drop the team mascot, Chief Wahoo, as its logo and will eliminate the character from its uniforms in 2019. For decades, the caricature of a grinning brave has been denounced by many Native Americans as racist.

The decision was made after negotiations between the Ohio team and MLB officials, who held that “the logo is no longer appropriate for on-field use.”

Ray Halbritter, an Indian activist who leads a campaign against such symbols, hailed the move. “The Cleveland baseball team has rightly recognized that Native Americans do not deserve to be

Yet Halbritter and other activists aren’t satisfied. They have also been calling for the team’s name to be changed. Indians owner Paul Dolan says that won’t happen.

The issue is the latest in a decades-long debate over the use of Native American-derived names, mascots, and symbols in sports. Today, about 2,440 U.S. sports organizations employ them, according to Terry Borning, an expert on mascots. That includes pro franchises like hockey’s Chicago Blackhawks and football’s Washington Redskins—as well as colleges and elementary, middle, and high schools.

Many such teams defend their Indian names and mascots as a vital part of their tradition. But critics say that they perpetuate outdated and offensive stereotypes about America’s