Sam Sandoval at age 19 in 1942 (left) and as he is today.

For 12 years, Sam Sandoval was forbidden to speak his own language. Like many generations of Navajo, he was sent away from his home in New Mexico to a boarding school as a child. There, he was forced to abandon much of his native culture and speak only in English. Sandoval and his friends “used to sneak away and talk Navajo,” he says.

Then, on December 7, 1941, Japanese planes attacked the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The assault killed more than 2,400 Americans and plunged the U.S. into World War II (1939-1945) against Japan and its allies. Like millions of other Americans after Pearl Harbor, Sandoval signed up to defend his country, enlisting in the Marines at age 19.

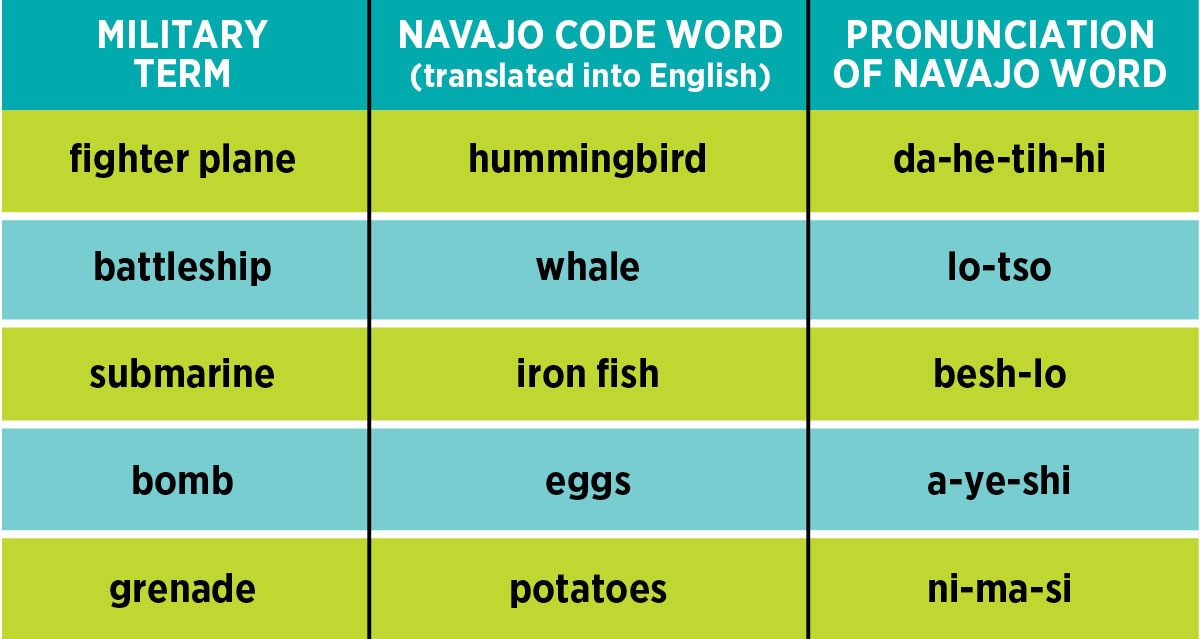

But he wouldn’t be an ordinary recruit. To his surprise, the Marines chose him for an experiment: to help devise and use a secret code based on the Navajo language. Sandoval would become part of a legendary group of some 400 Navajos known as the code talkers. Their unbroken code helped turn the tide in key battles in the Pacific Ocean (see map, below) and win the war against Japan.