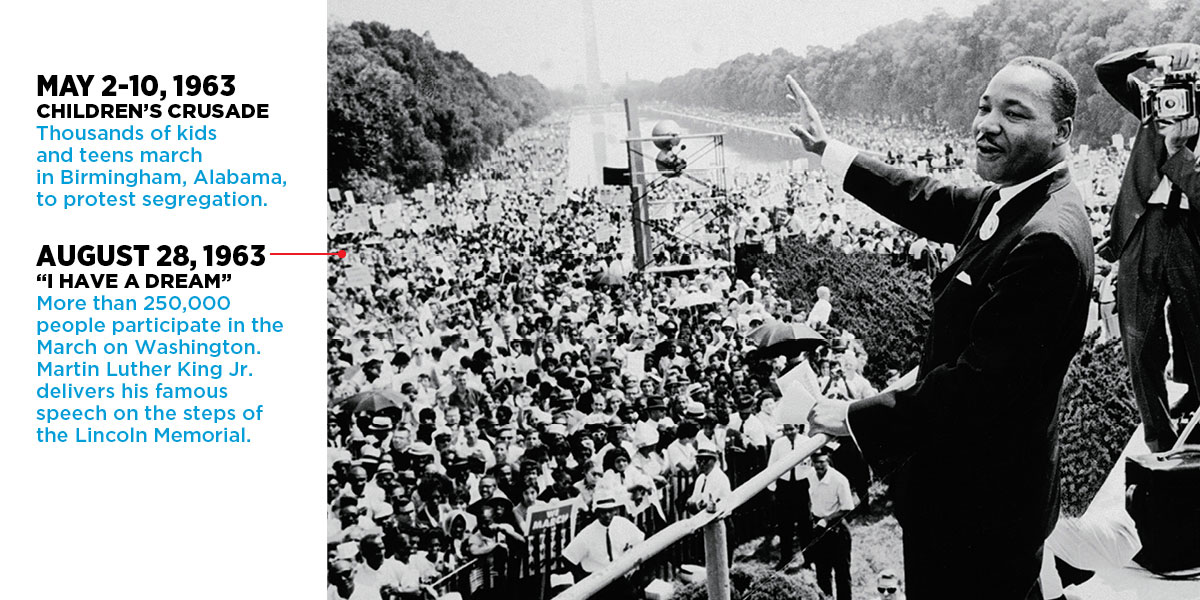

His words were an impassioned call for racial equality for African Americans. At the time, in parts of the country—especially in the South—Black people couldn’t eat at certain restaurants, continued to attend segregated schools (though the practice had been outlawed years earlier), and were unemployed at a rate nearly twice that of white people.

The march—a prime example of the nonviolent protest King advocated—helped secure passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. That landmark legislation outlawed racial segregation in schools, the workplace, and at public facilities. The act was one of many civil rights milestones in which King played a key role (see timeline, below).

But just a few years later, as King was shifting his attention toward poverty issues and housing rights for African Americans, his life was tragically cut short. On April 4, 1968, he was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee, at the age of 39.

Millions around the nation mourned King. “The heart of America grieves today,” said President Lyndon B. Johnson.“A leader of his people—a teacher of all people—has fallen.”

Today, as the United States marks the 50th anniversary of King’s death, important strides have been made toward achieving civil rights for all Americans. But the nation continues to struggle with racial discrimination. Even as King’s legacy has influenced a new generation of activists, his long-ago dream of equality has yet to be fully realized, says Hasan Jeffries, a professor of African American history at Ohio State University.

“The very same issues that people are wrestling with now—police violence and unarmed African Americans being killed, people taking to the streets for affordable housing—are the same issues King was wrestling with then.”