Dorothea Lange was beyond exhausted. It was a cold, rainy March morning in 1936, during the height of the Great Depression (see "A Decade of Struggle," below). The photographer had been on the road for weeks without a break, capturing the plight of struggling farmers with her camera. Driving up a long stretch of California highway past fruit and vegetable fields, she was in a hurry to get back to her home just outside San Francisco. Near the town of Nipomo, she passed a hand-drawn sign: Pea-Picker’s Camp. Lange considered stopping but didn’t. She had all the photos she needed for this trip, she thought. Then, 20 miles on, she turned back.

“I was following instinct, not reason,” Lange later wrote. “I drove into that wet and soggy camp and parked my car like a homing pigeon.”

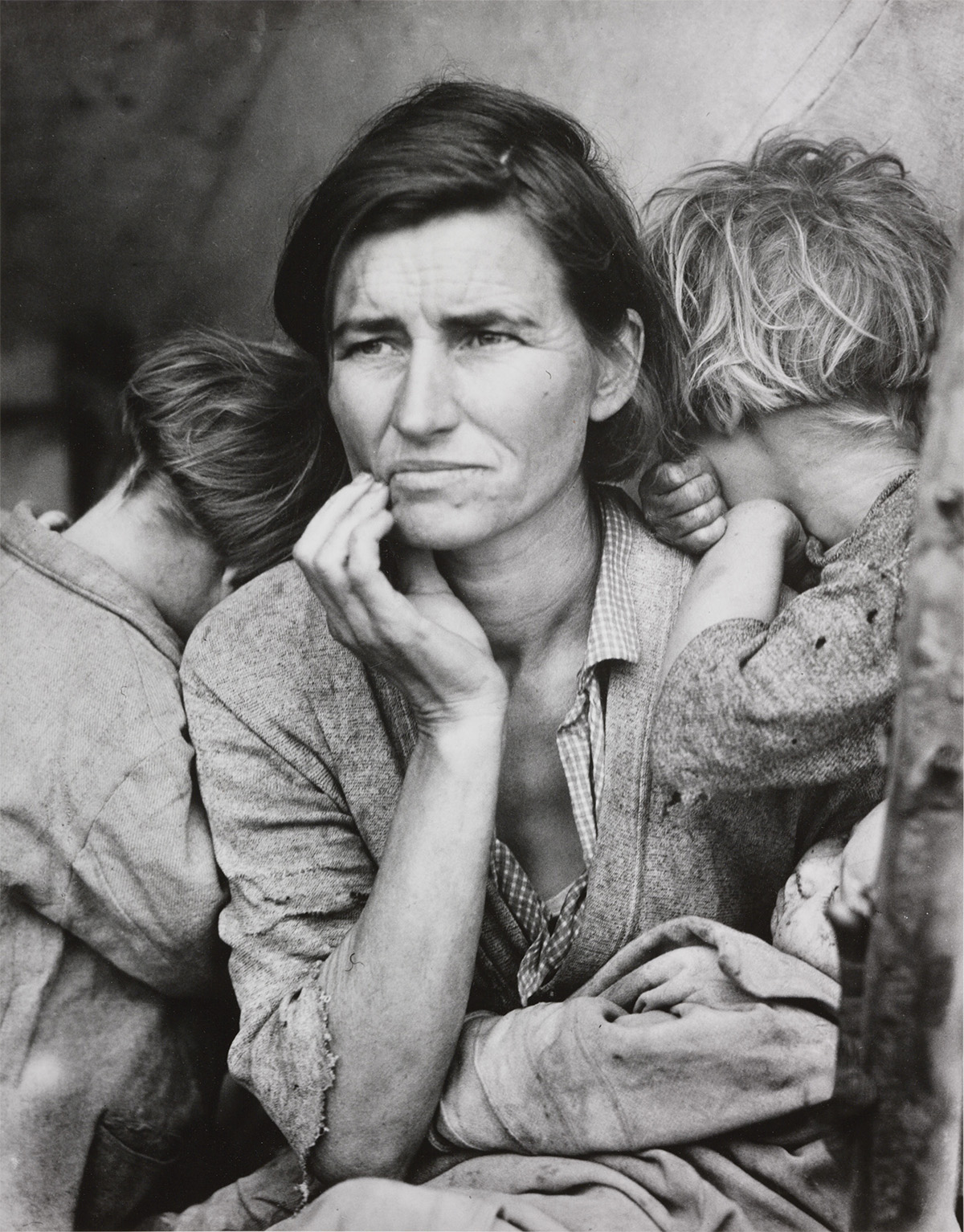

Approaching with her camera, she found 32-year-old Florence Owens Thompson and several of her children living in a makeshift tent. Like thousands of other migrant families, Thompson’s had fled drought-stricken Oklahoma, desperately looking for work on California’s farms. But weeks of heavy rain had kept them from picking peas as they had hoped, and then frost had killed the crop. The family had no money, their car had broken down, and they were reduced to scavenging the frozen fields for scraps to eat.

Lange’s encounter with the family was brief. She took seven pictures of Thompson and her children, then left. But the impact of those photographs is still felt to this day, scholars say. Lange helped change the way people around the world viewed those who were suffering during the Great Depression. One close-up shot of Thompson, eventually known as Migrant Mother, would become symbolic of hard times and human resilience. It is also one of the most famous photographs ever taken.